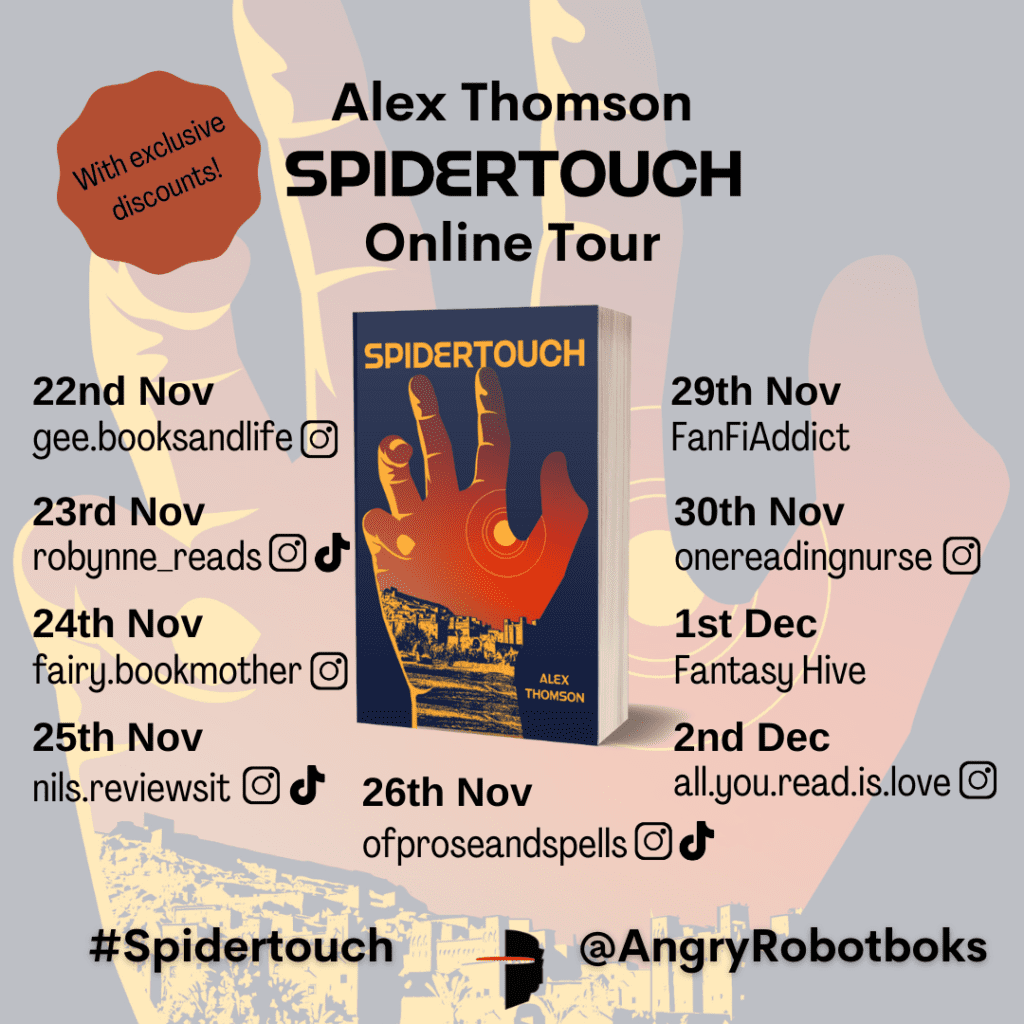

In honor of the release of Spidertouch, we have a guest post by Alex Thomson. You can preorder his new novel on the new website for Angry Robot Books, use code fanfiaddict to save 25% on books until December 4th, 2021!

The Original Lockdown: Siege Life in Popular Culture

I was halfway through writing my fantasy novel when the first lockdown struck. The setting was a city under siege, but I hadn’t planned to make the siege a major feature – it was just the background noise, and a plot device to keep my characters trapped in their own hellish huis clos. Being stuck indoors for twelve weeks, however – daily outside exercise notwithstanding – was a powerful insight into how claustrophobic life under siege must have been. So I ended up making the siege itself, and how the characters coped in it, play a much larger role. It also got me re-reading and re-watching some of my favourite sieges from fiction and film.

It’s noticeable that one of the most gripping elements of siege fiction is not themechanics – the rams, the trebuchets, the sappers (unless you’re a Sharpe-loving military fiction buff) – but the nightmare endured by the defenders. Our invaders are camped outside, pummelling the walls at their leisure, counting on the gradual starvation and panic inside to take its toll. The trauma withinthe walls is what really drives the story. Consider one of the first sieges in fiction – Troy, immortalised in both The Iliad and The Aeneid. When the Trojans drag in the Greeks’ wooden horse, Virgil explains it as fate and the Gods’ will, but I see a far more mundane excuse: a load of sleep-deprived and emotionally drained people exercising poor decision-making. In most sieges in modern fantasy, it is interesting to see how often the defenders are resigned to defeat. There is an inevitability to it – the only hope is surviving long enough for relief to arrive. In Legend, David Gemmell’s tale of the defence of DrosDelnoch, this fatalism is shared by all, even the hero Druss. Everyone is agreed they don’t stand the slightest chance of success, and yet the walls must be defended, and the reader alone holds out a glimmer of hope that Drusswill drag them to the impossible by sheer force of will. There are six walls, abandoned one by one as the defenders retreat to the final fortress, and their names are a delight, mirroring the emotions of the defenders at each stage: Exultation – Despair – Renewed Hope – Desperation – Serenity – Death.

Another favourite of mine is Joe Abercrombie’s Before They Were Hanged, and the siege of Dagoska. As always in fantasy sieges, the attacking army is an endless sea, wave upon wave of Gurkish troops crashing against the walls without any visible dent in their numbers. Superior Glokta exhorts and drives the defenders, every day of survival a mini-victory, and when the city falls, he flees and prepares to pay the price for his inevitable failure. His boss Archlector Sult is remarkably cavalier, though: “The best I was hoping for was that you’d make the Gurkish pay.” The epic battle for Dagoska is punctured – the unnecessary deaths of tens of thousands, no more than a trump card to play in the political machinations at the Open Council. Part of this inevitability is dramatic tension, of course – many medieval sieges would last years, and the reality of siege life would make for dull fiction. But I think it is also true that non-stop bombardment, never knowing where the next attack will fall, would play hell on your nerves and hopes for survival. Ultimately, though, most walled cities or castles must fall, or we don’t get the climax that a siege demands. A good counter-example is in A Game of Thrones, which features my favourite example of a dominant off-stage character: Stannis Baratheon, a brooding, dour figure who lurks out of sight throughout the first book of A Song of Ice and Fire. He is defined by his iron will, and everyone’s favourite Stannis anecdote is how he succeeded in holdingStorm’s End for a year under siege – reduced to eating the horses, then the cats, then the rats. We are left in awe of his grim refusal to buckle, to survive for months despite the psychological trauma of siege life. Not all fictional sieges call for such stoicism, however. Rather than being about passive endurance, many have a whack-a-mole feel to them – the enemy chipping away at different corners, the defenders stretched thin as they deal with each new assault. It is what makes Sixteen Ways to Defend a Walled City such a successful fantasy novel – the engineer Orhanconstantly inventing strategies to deal with each fresh threat, armed with a coil of rope, a bucket of nails and a willingness to lie, trick and cut various Gordian knots. More than any other type of battle, a siege is not about sheer numbers or brute force – it’s won by strategy; and occasionally cheating.

This also suggests why traditional sieges have not been so successful on film – Hollywood has little patience for this kind of drawn-out cat-and-mouse game between invaders and defenders. The sieges of Helm’s Deep or Minas Tirith are probably the most famous – but they barely qualify as sieges, impressively cinematic though they are – essentially, a helluva lot of orcs rock up andtry to storm their way over the wall. Where is the delayed gratification, the mind games as the months tick over? Instead, on film, the preference tends to be for what we might call “domestic sieges” – which can run on a faster timescale, and still tick the box of dramatic tension. Straw Dogs is a classic example,which sees Dustin Hoffman racing round his Cornish farmhouse, keeping out the local yokels who want to break in and deliver mob justice to his guest. He even lays some traps – burning oil, a primed beartrap – in a kind of horrific, not very light-hearted version of Home Alone. “I will not allow violence against this house,” he intones to his wife, deadpan. I remembered Home Alone, incidentally, as a zany romp, but when I watched it as an adult, I was struck by the undertone of menace (I mean, I know it’s Joe Pesci, but still – “I’ll kill the little prick…” probably would raise a few red flags these days). It’s a textbook whack-a-mole siege, Culkin dashing upstairs and downstairs, keeping the thieves at bay with different traps and tricks. Panic Room, on the other hand, is a similar idea, but swaps slapstick for terror. It evokes perfectly that fear of being surrounded, and Jodie Foster is unable to sleep or relax, no idea where the next attack might come from – Fincher uses the security cameras to brilliant effect, with the invaders creeping in and out of the grainy footage.

It seems remiss not to mention macho Steven Seagal vehicle Under Siege, but I couldn’t bring myself to re-watch that, so instead I’ll finish with a truly unusual siege: Cujo, the 1981 novel and 1983 film. Only Stephen King could pull off something as bravura as a siege in a car – a mother and child trapped inside a few cubic metres by a rabid dog. See also Misery and Gerald’s Game– both protagonists spend most the novel in a bed, either injured or handcuffed: King’s novels of that period are often about being trapped, both physically but also by your past, and the siege mentality it creates in your psychology. Cujo is an assault on the senses, as the giant Saint Bernard smashes against the Ford Pinto, and Donna has to ride it out, for the sake of her son. The ending is brutal, and a reminder that most siege survivors will have demons to face, long after the battle has ended.

About the Author:

Alex Thomson is the author of Death of a Clone, published in 2018. He lives in Letchworth Garden City – home of the UK’s first roundabout – and his day job is a French and Spanish teacher in Luton.

About SPIDERTOUCH (available December 14, 2021):

Enslaved by a mute-race of cruel dictators, Razvan learns their touch-language and works as a translator in order to survive. But war is on the horizon and his quiet life is about to get noisy…

When he was a boy, Razvan trained as a translator for the hated Keda, the mute enslavers of his city, Val Kedić. They are a cruel race who are quick to anger. They keep a tight hold on the citizens of Val Kedić by forcing their children to be sent to work in the dangerous mines of the city from the age of eleven until eighteen. By learning fingerspeak – the Keda’s touch language – Razvan was able to avoid such a punishment for himself and live a life outside the harsh climate of the slums. But the same could not be said for his son…

Now a man, Razvan has etched out a quiet life for himself as an interpreter for the Keda court. He does not enjoy his work, but keeps his head down to protect his son, held hostage in the Keda’s mines. The Keda reward any parental misdemeanors with extra lashings for their children. Now the city is under siege by a new army who are perhaps even more cruel than their current enslavers. At the same time, a mysterious rebellion force has reached out to Razvan with a plan to utilize the incoming attack to defeat the Keda once and for all. Razvan must decide which side to fight on, who can be trusted, and what truly deserves to be saved.

Leave a Reply