If you have a pulse and enjoy anything close to horror, odds are you’ve heard the immense buzz around Oz Perkins’ latest film, Longlegs. The focus of this box-office hit is a string of bizarre, unsolved cases thought the be committed by a serial killer known as Longlegs. If this very short synopsis doesn’t ring a bell, this article may not be for you as this is a very deep examination of one of the central characters of this film, Special Agent Lee Harker. While it’s typically the serial killer who haunts the minds of viewers of a film like this, I can’s say this is true of Longlegs with Maika Monroe’s portrayal of Lee. Here’s your last spoiler warning.

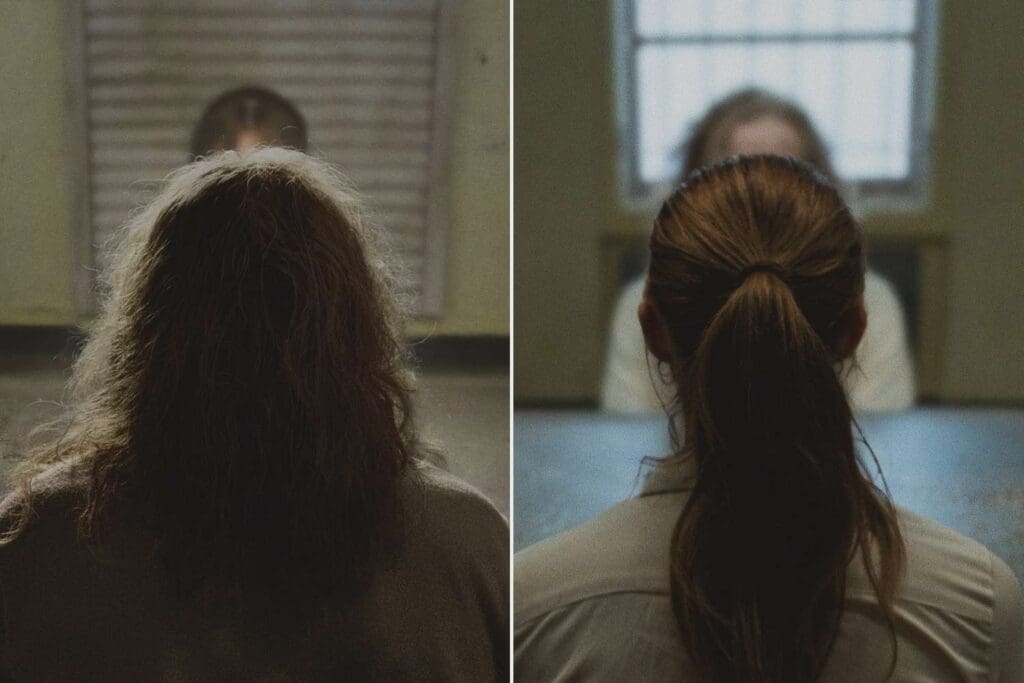

Armed with an uncanny ability of foresight, Lee Harker is a young woman who looks haunted from the very moment we lay eyes on her. The opening scene of the film is bleak and jarring, painted with a stark palette that expertly places viewers on the edge of their seats before any real events transpire. It’s an ideal set-up that juxtaposes the drab setting of an FBI briefing in which we first see a grown-up Lee. Here is where Perkins’ intentional symmetry and profoundly precise direction begins to make itself known. Framing buildings and characters either equally lateral or as the sole subject of each shot, we get the subliminal message of an inverted triangle, Longlegs’ signature to commune with the devil. The white color scheme presented with Longlegs while the darkness surrounds Lee. All within the first few minutes of this film many themes writhe in the darkness of our subconscious.

Longlegs and Lee seem to have a dark, disturbing “yin and yang” relationship that is unknown to Lee until act three and behaves in a way that most wouldn’t expect. While she is not consciously aware of this connection, later revelations suggest there’s an unconscious recognition on Lee’s behalf to this kind of malevolent “other.” It adds to the weight that she carries without us really even realizing it, the way she presents herself so sternly yet affected. Most folks predicting the exact location of a killer without any concrete evidence would give pause to their premonitions, but not Lee. Sure, we can argue there’s some neurodivergence at play here with her character, but it’s not something that’s ever labeled or even mentioned, the way it should be. Lee is Lee, someone who abides by the logical rules she’s come to know from her unconventional past. There’s no air of pretense with her character, no social camouflage she utilizes to navigate her world. At her core, she presents as an earnest individual as given her conversation with Ruby Carter:

Ruby Carter: “Is it scary being a lady FBI agent?”

Lee Harker: “Yeah. Yeah, it is.”

The catch with Lee comes in the form of her familial ties, her mother. The investigation into Longlegs progresses, and it becomes overly apparent there is a personal tie between the Harkers and this killer. While Lee is prompt to share her findings related to Longlegs’ algorithm with her superior, Agent Carter, at the FBI, she is hesitant when matters pertain to her mother, Ruth. Lee’s first visit home marks another drastic opposition in character; where Lee’s home is sparse and seemingly unlived in, Ruth’s home is full of clutter. Ruth’s language is fantastical, seeming to only speak in riddles to where’s Lee’s speech is clipped and logical. Remarks are made in which it becomes abundantly clear that Ruth suffers from an inability to let anything go regarding Lee, physically, emotionally, or otherwise (plus those teeth we see in plastic baggies). It’s a bit of a jarring presentation given what we know of Lee, the disciplined law enforcement agent with a knack for sensing what others cannot. And this is where she haunts me, especially when reflecting on the archetypes of strong female leads working in law enforcement presented in media who precede her.

The idea of a “just” morality with strong female characters in law enforcement is nothing new in the eye of entertainment. However, it’s something that doesn’t necessarily apply to Lee in the ways we’ve come to think of those who came before her. We’ve seen multiple female leads in television and film who fight the good fight in the name of what is right, what is morally just. But the jaded, complex, and possibly morally-ambiguous woman with a badge and gun seem to be a trend in recent presentations.

An example of this comes in the form of Clarice Starling (The Silence of the Lambs) who showcases immense bravery and self-sacrifice in communicating with Hannibal Lecter, all in the name of catching Buffalo Bill. She’s an admirable FBI agent who goes above and beyond in the realm of law enforcement and even manages to save the day. It’s a little hard to compare Clarice and Lee given their stories focus on some differing aspects. The Silence of the Lambs is a film that is investigation-heavy and showcases the complexities of being a woman who exists in a male-dominated field. Clarice is memorable for her ability to adapt to whatever situation she finds herself in, her ability to be bold, and her nobility. She stands out for her ideas of resiliency, tenacity, and well, righteousness.

Another example is Dana Scully (The X Files), another overachieving, morally “correct” woman who not only works for the FBI, but holds a medical degree. A large part of Dana’s character arc focuses on her idea of the fantastical as it does not align with her faith. Much of Dana’s character development and characterization is built upon the things she can accept which is largely defined by her sense of morality. That little gold cross around her neck holds a lot of weight across eleven seasons of television and two movies. And listen, I get it. We want to like our strong female characters with ease. However, the truth is not so simple.

Here’s where I feel a divergence in recent times, the era of a new kind of archetype emerging to take center stage. Complex characters with questionable motives, dark pasts, and jagged edges have always captured attention. Yes, Clarice and Dana are compelling in their own right, but for very different reasons than the presentation of characters like Liz Danvers (True Detective: Night Country) and Lee Harker. There’s a reality to these haunted, somewhat tortured women with immense levels of depths.

This shift in presentation is a welcome change in my opinion, one that lends itself to the authenticity of the horror genre in particular. With Issa Lopez at the helm of True Detective: Night Country, we were given Liz, a seemingly harsh woman with a lot of scars and a lot of story to tell. This haunting past that lurks over her shoulder proves to motivate Liz in ways that don’t always align on the correct side of the law despite her position as a cop. These complexities born of trauma supply grit to Liz, give her an edge that maybe hasn’t been as exposed in previous works of horror or crime media. These complexities that add such dimension are similar to those expertly executed by Oz Perkins with his creation of Lee Harker, a young woman confronting the sins of her mother’s past.

Classifying Lee as a morally gray character feels disingenuous, but she doesn’t fall in line of the squeaky clean hero either. Perkins leaves LOTS of room for speculation with this film, and here is where my theorizing begins. Given the strength of her abilities, Lee’s avoidance of her mother feels intentional. It’s hard to find a solid reason for the clipped, strange phone calls we see Lee make to her mother, but it is very clear that something is amiss within the first few scenes of the film. As stated previously, Lee’s homecoming trip is a stark contrast to her independent life. But most notable is the conversation had between Ruth and Lee, Ruth begging the question, “Do you still say your prayers?”

This is the moment that a clear difference is noted in Lee compared to some of the leading ladies who have come before her. She says no. There’s no air of remorse, no covering up the fact that she does not subscribe to her mother’s fanaticism. Just a clean, resounding, “No.” Remember that earnestness? From here, a marked shift comes about as Lee walks to the kitchen to make tea, taking stock of a door that’s locked. A ring of keys with endless possibilities beside it. And what does Lee do? She tries to open that door.

To say that Lee is complicit in Longlegs’ crimes feels like a stretch. Yet, she does pump the brakes and exhibits unprecedented uncertainty regarding her mother’s role in Longlegs’ mission. This hesitation is further magnified in the final scene of the film in which all the pieces fall into place. Lee does not immediately eliminate the threat of the doll upon entering Agent Carter’s home. Rather she converses with her mother and allows Carter to walk away and kill his wife. Lee is brave, bold, and intelligent, but her nuance stems from her natural fear that is expressed so clearly with no air of doubt. This is an organic fear of rejecting the reality that her mother killed so Lee could live. Fear of the harsh reality that has earned her life. Fear of realizing she must kill the thing she knows so intimately, yet cannot fully escape.

Longlegs to Lee: “I know you’re not afraid of a little dark. Because you are the dark.”

Longlegs is a lot of things especially when examined in the scope of pop culture. At times, it feels satirical mocking the state of horror with plenty of room for jump scares but rarely executing them. It also stuns as a twisted crime thriller with tones of horror exacted by Nicholas Cage’s demented Longlegs. It can be classified as a horror film that revels in the darkness of capitalizing on and manipulating innocence. But on a subliminal level, it’s a deeply dark look into the painstaking battle of crawling out from under your parent’s shadow as exhibited by Lee Harker, a not-so-perfect hero. Her expressed fear, the building dread as layers of the truth are revealed, and the eventual nightmare of reckoning with her mother in the final act paints Lee in such an intriguing light especially when compared to Longlegs himself. You could make the argument that Longlegs is staving off parental issues in his own twisted way, claiming Satan as his true father as exemplified by his screeching outburst in his car about mommy and daddy.

Whatever your thoughts may be on Longlegs, one thing remains true; this is a haunting film that may linger for reasons you may have not expected. Oz Perkins crafts this very wretched film through the constant subversion of expectations which are made possible thanks to actors like Cage and Monroe. It’s in this very way that Lee Harker is the character that latches onto my fascination most. She’s hard to define in words but is ultimately feels like a departure in our well-loved, strong female leads within settings of law enforcement and horror. It’s an arresting shift in narratives that has satisfied me to no end and will surely provide a multitude of gripping stories to come. Take it from a friend of a friend.

Now, if you’ve read this much, kudos for sticking it out through my rambling, wandering examination of this film and one of its titular characters. As someone who normally provides analyses of books rather than films, it feels criminal to go without some read-a-likes for Longlegs so here’s a list of recommendations I’ve compiled which fall into similar themes for one reason or another:

– The Cases That Haunt Us – John E. Douglas and Mark Olshaker

– The Silence of the Lambs – Thomas Harris

– Come With Me – Ronald Malfi

– Dear Laura – Gemma Amor

– Penpal – Dathan Auerbach

– Chasing the Boogeyman – Richard Chizmar

– The Vein – Steph Nelson

– None Shall Sleep and Some Shall Break – Ellie Marney

– The Nightmare Man – JH Markert

– The Book of Accidents – Chuck Wendig

– Looking Glass Sound – Catriona War

-The Whisper Man – Alex North

– Lost Man’s Lane – Scott Carson

– Letters to the Purple Satin Killer – Joshua Chaplinsky

Leave a Reply