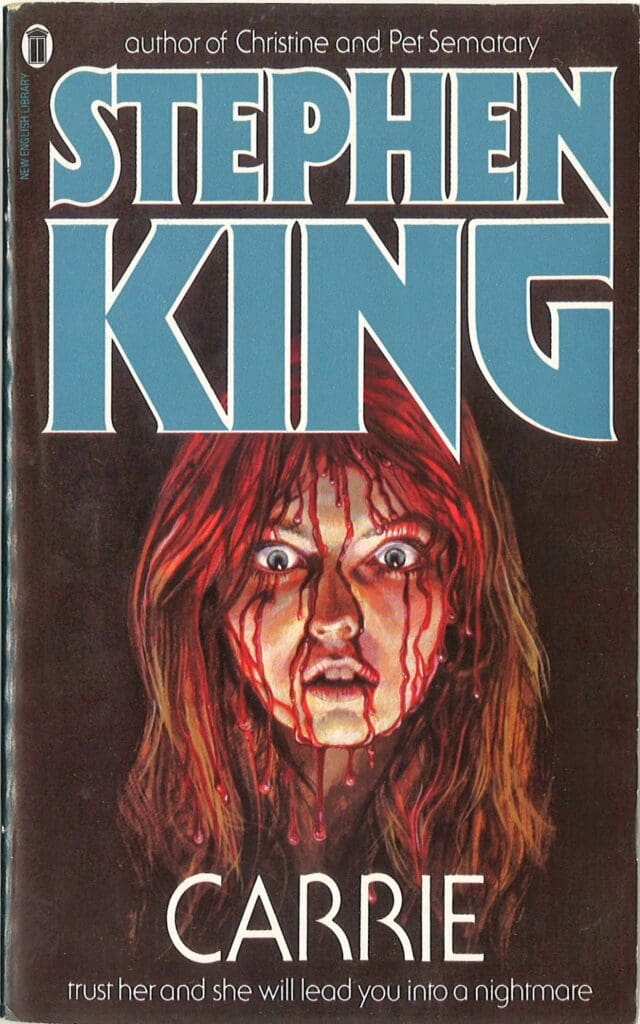

Perhaps the most shared sentiment among Stephen King fans that I’ve come across when asking if someone has read this book or that by King is the response, “Oh yeah, I read that when I was like ten years old. Way too young to have read it, but I loved it.” While I can say I’ve watched and read my share of inappropriate things in my childhood, I unfortunately cannot say that those items include the works of Stephen King. It wasn’t until high school that I first read The Shining and even later in college that I picked up Pet Sematary. An even larger gap existed in which I didn’t decide to read The Body until grad school, and my hiatus finally reached a conclusion in the fall of 2022 with Doctor Sleep. Since then, my diet of King’s works has been steadier and with this influx of consumption also grew my appreciation and admiration for his writing. While my young brain may have not been influenced by Pennywise, Carrie, or Cujo, I’m beginning to find that my adulthood is thriving on the horrors found in Derry, Chamberlain, and Castle Rock.

In a way it feels wrong to review a work of King’s; minds far more well-versed than I have dissected, critiqued, and debunked many of his works since the release of Carrie in 1974. However, reading always has been and always will be a unique, personal experience that varies from reader to reader across the landscape of time. And here’s where the idea of this (and possibly future?) essay(s) comes into play; reading the works of King in adulthood feels like a unique privilege, especially during this boom of contemporary horror fiction. Reading the works of Nat Cassidy, Jonathan Janz, Chuck Wendig, and Catriona Ward (I could keep going, this is a very long list) has been extremely impactful in my life and has shaped my current worldview. Yet, a common vein of “Kingian” writing can be found in so much of the literature I consume today. So why not visit the source?

Carrie (1974)

April 5, 2024, marks the 50th anniversary of Stephen King’s debut novel, Carrie. In the spirit of celebrating such a landmark, numerous authors, podcasters, and other writers have decided to embark on deep dives into this inaugural work of horror fiction from the king of horror himself. Of course, this has generated much excitement and prompted my own decision to read Carrie for the very first time. As a twenty-five-year-old female, I prefaced this read with some apprehension. Carrie was published back in 1974, a time in which the world looked a lot different for women. My core beliefs and personality hinge upon the empowerment of women and our constant struggle for autonomy so you can probably understand my unease in opening to page one of a novel written by a white man in the 70s. However, I can honestly say I was completely and utterly blown away.

Of course, this novel is not without its flaws in terms of how dated some of the passages read in terms of descriptions of women and race. Such a thing is expected in King’s work from this time, but I would be remiss in not mentioning so. Despite its short length (especially in comparison to King’s later works), Carrie covers a vast amount of ground in a confined space. This is perhaps what astonished me the most, how much commentary was provided about religion, womanhood, conspiracy, retribution, anomalies, and cruelty. Even more intriguing is the formatting of this epistolary novel, a tapestry of interwoven reports, passages from publications, and narratives. So much horror today is created in the vein of “found footage” scenarios in which an event is retold through recordings, photographs, or other media. While I wouldn’t say Carrie falls in this category directly, it is clear to see the lineage between the two.

“Carrie obediently raises her hands and plucks her head from her shoulders. Hands it to Sheriff Doyle, who solemnly puts it in a wicker basket marked People’s Exhibit A.”

The mental musings of Sue Snell, a classmate of Carrietta White, on that infamous prom night, deliver one of the clearest summations of the novel. Carrie has long been the subject of persecution by her classmates for being “other.” Her skin is not clear, she is not thin, she does not have friends, her mother (and subsequently Carrie) often damn others to hell, and she is labelled as “other.” This is all before any mention of her telekinetic abilities, her rejection stemming strictly from normal, human traits. The bottled, perceptive experience of high school has the power to reign supreme as “The Glory Days” for some while also being characterized as hell on earth for so many others. You may never be judged as harshly as your years in high school, not unlike the imaginary instance Sue conjures for Carrie as stated above. Day in and day out, Carrie was placed on social trial in the halls of Ewen High School, something that feels as though it is the truest example of the haves and the have-nots.

“High school isn’t a very important place. When you’re going you think it’s a big deal, but when it’s over nobody really thinks it was great unless they’re beered up.”

We meet Carrie in one of the most humiliating and eventually degrading moments imaginable; she begins her first period in the school showers, naked and exposed to the female population that mocks her. While this feels embarrassing on the surface, we come to understand that Carrie has no earthly idea what menstruation is or what it means. The sheltered, religiously traumatic upbringing her mother has provided for Carrie only breeds room for misunderstanding and confusion to the point where Carrie believes she is actively bleeding out and dying. Horrific enough, yes, but the terror does not end there. Like sharks smelling blood in the water, Carrie’s classmates meet her hysterical screams with mockery, throwing tampons and pads at her while her panic ensues. Most horrific of all, not a single soul puts an end to this persecution until the gym teacher herself steps in. Beyond this scene, a great sense of importance is linked to this singular event, especially given that Carrie’s telekinetic powers emerge in tandem with her firm entrance to womanhood.

Between this scene and that of Sue Snell finally receiving her period on prom night in the wake of the town’s destruction, this weight of womanhood cannot be ignored. There are a few ways this emphasis can be taken, but my personal (and maybe overly optimistic) view is King’s recognition of the struggles of womanhood. From the female perspective, the brutality of the locker-room scene cannot be overstated and feels symbolic of the cruelties the female gender endures time and time again. This sets the tone for the rest of the novel, one of heartbreak for Carrie, dread for her future, and hatred for the cruelty she faces in all corners of her existence.

“‘I only want to be let to live my own life. I…I don’t like yours.’”

What is essentially a simple line, a simple wish for Carrie, delivers such a devastating blow in the context of her desire for her own agency in the eyes of her zealot mother. Margaret White’s staunch worldview and subsequent harsh child-rearing practices thrive on abuse and punishment in the name of constant atonement for sins. As far as Margaret is concerned, her mere existence (and Carrie’s) as a woman is a sin in and of itself, instilling a sense of tremendous loathing and hate within the White household. This strikes an extremely personal chord, especially through the lens of religion. How can a whole gender be faulted for simply existing in space? Must we truly atone for each breath we take since we reek of corruption and sin? While no religion states these judgements plainly, it is clear to see the blatant instances of sexism through other dogmas, teachings, and parables across faiths. This idea is magnetized in Carrie’s home life which can be defined as a particularly ruinous existence. Truthfully, I can’t think of bleaker circumstances, especially as the events of the novel transpire and we see the lengths Margaret, Carrie’s own mother, is willing to go to in the name of righteousness. Rubbing salt into this particular wound is Carrie’s love for her mother and her desire for her approval, despite deciding to act in favor of herself. It is literally with Carrie’s dying thoughts that she still thinks of her mother, how she yearns for her forgiveness when it could be well argued that Margaret directly contributed to this mass devastation of prom night. Her own daughter’s ruin.

“Girls can be cat-mean about that sort of thing, and boys don’t really understand. The boys would tease Carrie for a little while and then forget, but the girls… it went on and on and on and I can’t even remember where it started anymore.”

Female intolerance has long been an intriguing phenomenon that, unfortunately, remains constant. Carrie delves into the deepest, darkest horror that thrives in the space where women attack women. The character of Chris Hargensen exemplifies the cruel and calculating nature in which this female cruelty shines through her plotting of prom night, the infamous bucket of pig’s blood to be dumped on Carrie White’s head. From the inception of this plan, King takes a deep dive into the horrors that persist for the remainder of the novel, beginning with the execution of the pigs themselves. While this act of violence is done by her right-hand man and boyfriend, Chris goes to great lengths to ensure that Carrie is crowned prom queen for the sole purpose of exacting her form of punishment. And, again, what did Carrie do to deserve such treatment other than exist? Something deeply disturbing lies at the bottom of that bucket of blood, the idea that one gender can hate its own so deeply to maim and attack another in such a way. Possibly, what is even more frightening, is the ease of group influence and how quickly the other students fall into laughter at Carrie’s expense. I can’t help but wonder, what would Sue Snell have done had she been there?

“She was glad they had decided to leave her alone, because she was still uncomfortable about her own motives and afraid to examine them too deeply, lest she discover a jewel of selfishness glowing and winking at her from the black velvet of her subconscious.”

On the opposing side of this spectrum from Chris, Sue wouldn’t be classified as a friend of Carrie’s, but she seems to be the only “remorseful” character in this whole novel. She is perhaps the second most interesting character involved in this whole affair as her guilt and subsequent actions toward penance are closely examined. She asks her own boyfriend, Tommy, to take Carrie to prom following the locker room incident. But truly, what is her motivation behind this decision? Is it to offset her own guilt or because she truly understands the harm done to Carrie? And is her guilt “enough” to declare her an ally of Carrie? Much of Carrie is written in terms of righteous justice, from Margaret’s outlandish cycle of repentance to Carrie’s journey of destruction, making Sue’s place in the matter rather fascinating. A lot of discussion has been spent on Carrie’s morality and if she is truly evil, but I’m nearly as intrigued by this young woman as Carrie. Even as a morally grey character (that sides closer to the light), Sue Snell is one of the only surviving individuals from prom night and one of the only defenders of Carrie following the decimation of Chamberlain. Despite her decision to send Tommy to Carrie, in essence fueling the fire to come, Sue searches for Carrie in the ruins of the town and spends Carrie’s last dying moments with her. I honestly think my mental wheels will forever be spinning when it comes to Sue Snell and her role in Carrie’s end.

“If the TK test shows positive, we have no treatment except a bullet in the head. And how is it possible to isolate a person who will eventually have the power to knock down all walls?”

The idea of “anomaly” seems clearest with respect to Carrie’s telekinetic abilities and seemingly serves to elevate just how ostracized she truly is. As mentioned before, a lot of emphasis has been placed on just how deep the roots of Carrie’s violence grow. To that question, I can’t help but feel as though she is strictly a girl who has had more than her share of hurt, more than her share of suffering. Truthfully, I think Carrie can function as a horror novel without this paranormal influence. In fact, one of the greatest senses of pure dread while reading this novel stems from the slow building unease of prom night. This dramatic irony of knowing just how terrible things are about to turn but simply waiting it out… there are no words for that feeling King creates. And sure, the disaster of prom night would certainly be diminished without Carrie’s abilities, but King’s horror (time and time again) proves itself through the cruelty of human beings. The paranormal or supernatural he includes in his plots only supplement the dark undulating feelings already at play in a community, in this case, Chamberlain, Maine. There’s nothing otherworldly about taking a sledgehammer to a pig’s head, plotting the ruin of the school outcast, or repeatedly locking your child in a closet for simply existing. These are all starkly human actions that are only magnified by Carrie’s abilities through her night of “retribution” at the novel’s conclusion. Carrie’s story may be considered a revenge plot by some, but more importantly, it screams tragedy. This novel feels like the literary amalgamation of “death by a thousand papercuts” in which the meter for cruelty tops out at some point, namely resulting in the destruction of an entire city and its future at the hands of a teen girl who has been given too much to bare.

“No one was there – or if there was, He/It was cowering from her. God had turned His face away, and why not? This horror was as much His doing as hers. And so she left the church, left it to go home and find her momma and make destruction complete.”

Conspiracy runs amok in Carrie, not only through the government’s perspective and eventual burying of the details of Carrie’s wrath but also through the analysis of the events leading up to prom night itself within the high school environment. This novel functions in a way that feels as though we are searching for the truth of the matter, an investigation of sorts that aids in the rather fast pacing of this story. Frankly, I have never felt so gripped by a King novel prior to my reading Carrie, I could hardly put the thing down. Stephen King has always thrived amid an array of complex characters who interact with one another to varying outcomes of humanity and violence, the epitome of Carrie.

However, Carrie feels markedly different from anything else I’ve read from his backlog. The exposure to Carrie’s inner thoughts and dialogue, even through different characters at the end of the novel, peeled back the curtain so to speak. As readers, we are privy to Carrie’s struggle with her relationship with her mother, her vulnerabilities in deciding to accept Tommy’s invitation to prom, and the sheer amount of pain she endures following the events of that fateful night. The rage she experiences is literally deadly, and I can’t help but feel it is so rightly deserved. While this may initially feel like a “good for her” moment, further contemplation lands me squarely at heartbreak for Carrie given that she meets her demise as well. Carrie White’s last memories are those of savagery and violence, even from the one person she loves most. Even still, being subject to so much mistreatment, her retribution feels deeply cathartic as her experiences feel as real as our own while reading this novel. The idea of revenge and wrath, its justification or rejection, lingers in my mind and will probably do so for an indeterminate amount of time. But truthfully, how much can one girl take?

“Nobody was really surprised when it happened, not really, not at the subconscious level where savage things grow.”

Horror and heartbreak often work best hand in hand, a truth solidified by Carrie. In under three hundred pages, Stephen King has posed more questions regarding the substance of womanhood, what it means to feel guilt or true sorrow, the depths of cruelty, and the righteousness of revenge in the face of tragedy. More importantly, King establishes a deep of empathy for Carrie, a girl who faces sheer, unrelenting punishment for merely breathing. For these reasons and many more, this has become my favorite work of King’s (thus far). The balance of fear, heartbreak, dread, and demise culminate in a work that is truly unforgettable. My thoughts continue to drift to Carrie White, the girl who dared to exist.

Leave a Reply