Welcome to another Escapist Tours Book tour! This time it is for Warrior of Light by William Heinzen! Below you can find information on the book, the author, a guest post by the author himself talking about why the farm boy hero trope still works in epic fantasy, and a GIVEAWAY! Enjoy!

Book Blurb

Tim Matthias has only ever known the peace of the South, but that peace is shattered when a group of mysterious creatures destroys his home. In search of answers, Tim discovers the poisoned wastelands of the North, where the Dark Lord Zadinn Kanas rules over all. It is here that Tim joins forces with a band of freedom fighters on a quest to find the Army of Kah’lash, a mythical force destined to serve those in need. At the same time, Tim must learn to use the magic of the Lifesource, for he is the Warrior of Light. As Tim struggles to accept his destiny, those around him must battle their way across the North, seeking a means to wage one last, desperate stand against Zadinn and his armies…

Two Wizards Try to Blow Each Other Up • When You Don’t Have Enough Time to Read Sanderson • The Wrong Place at an Even Worse Time

Book Info

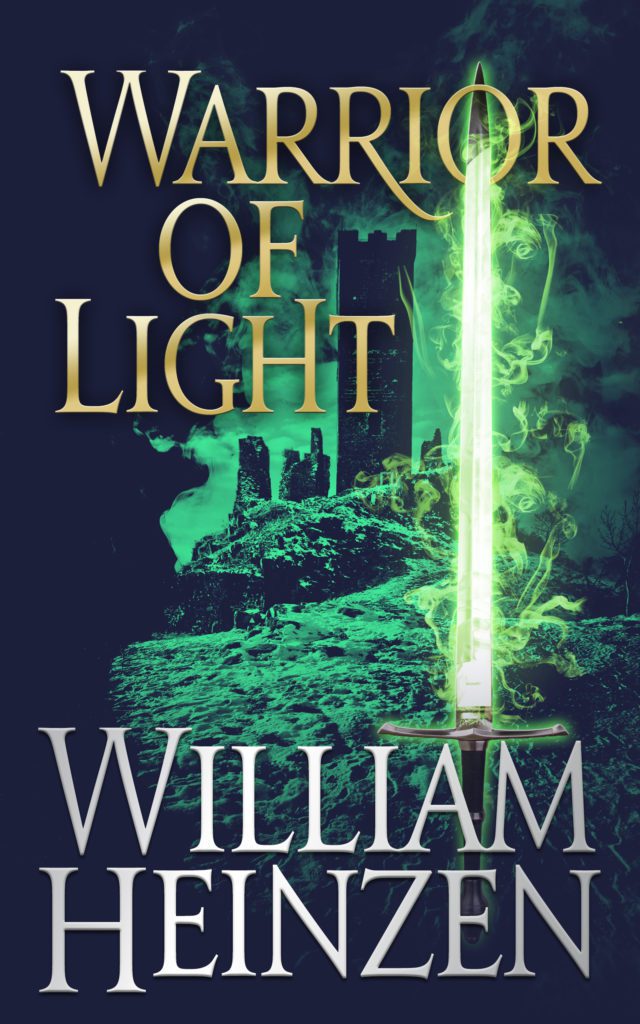

Warrior of Light by William Heinzen

Published: 2018

Series: Standalone with sequel

Genre: Epic Fantasy

Intended Age Group: 14+

Pages: 485

Publisher: Self Published

Book Links

Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/Warrior-Light-William-Heinzen/dp/0692769056/

Audible: https://www.audible.com/pd/Warrior-of-Light-Audiobook/B08VV6TVND

Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/33099250-warrior-of-light

Author Bio & Links

William Heinzen is the author of the epic fantasy novels Warrior of Light and City of Darkness, as well as the short stories Malichon Manor, Nightfall, and Shadows in the Snow. He has been a guest at FanExpo New Orleans, Tampa Bay Comic Convention, ValleyCon, and iMagicon. He has also presented at North Dakota State University’s Creative Writing Camp. William lives in Bismarck, North Dakota, where he works as a cybersecurity professional by day and writes by night. In 2018 he was named to Prairie Business Magazine’s “40 Under 40” list.Goodreads:

Author Site: https://www.williamheinzen.com/about

Twitter: https://twitter.com/thewriterbill

Essay: Why the Farm Boy Hero Trope Still Works in Epic Fantasy

It’s been nearly seventy-five years since Joseph Campbell wrote The Hero With a Thousand Faces, in which he described the concept of the monomyth or hero’s journey. Campbell did not invent this concept per se. Rather, he drew upon the studies of previous scholars like Carl Jung, who believed that collective human experiences could be categorized into various archetypes. We see this regularly in fiction. The “wise old man” or “mentor”, for example, is present in numerous narratives, be it Merlin, Gandalf, Obi-wan Kenobi, Dumbledore, or countless others. Campbell did not create the hero’s journey, but he did present it via an understandable framework that has been used in popular fiction ever since.

Naturally, there has been a reaction against the hero’s journey in more recent literature. Readers do not necessarily wish to read one more iteration of Star Wars or Lord of the Rings—take it from one whose debut novel, Warrior of Light, was described positively by one reader with the caveat that it had a “Jedi lost in Middle Earth vibe”. I personally find that a great tagline, for what it is worth, and yet by the same token I have also sought new experiences in literature. The characters of Frodo and Sam (Lord of the Rings), Belgarion and Belgarath (David Eddings’ Belgariad), Simon Snowlock (Tad Williams’ Memory Sorrow and Thorn), and especially the one and only Rand al’Thor from the late Robert Jordan’s Wheel of Time certainly hold a special place in my heart. The Wheel of Time was the most significant reading experience of my life, bar none, but I’m not necessarily looking to read another work that attempts the same thing. Let Jordan’s work stand on its own.

Thus, now we see fantasy literature of a new mold, most notably in the vein of works like A Song of Ice and Fire / Game of Thrones, in which any mentors are likely to be deeply flawed and to meet a grisly fate. I didn’t necessarily appreciate A Game of Thrones when I first read it, but only because I am a slow learner. I re-read it two years ago and finally understood what a phenomenal thing Martin had done. His command of prose was tight, his dialogue real, his plot fast-paced. Fantasy did not need to be a slow and plodding trek from point A to point B. It could blend relatable political intrigue against the backdrop of world-ending stakes. I have not read Joe Abercrombie’s work just yet, but it is on my shortlist for the next year, and I’m looking forward to what I believe will be hard-boiled prose, grit, and a story driven by the interactions of unpredictable but real characters rather than a formulaic outline. No spoilers!

This, of course, begs the question—why did I choose to follow rather standard hero’s journey fare when writing Warrior of Light? The basic structure of Campbell’s monomyth, truncated for brevity, is as follows:

– Ordinary hero receives call to adventure

– Hero crosses a threshold into a new world

– Hero gains a mentor, generally one with supernatural powers

– Hero overcomes obstacles escalating in complexity

– Hero reaches their darkest hour / mentor often dies

– Darkest hour results in hero’s transformation

– Transformation allows hero to defeat villain

– Hero returns home

Or, as more succinctly put by Bilbo Baggins, “There and Back Again”. We’ve all seen it before.

There are three reasons Warrior of Light follows this predictable pattern. The first two are brutally honest. First, I did not know how to tell any other kind of story; I was more concerned with putting together a coherent narrative than trying something new and daring. Second, I (like many writers) began writing because of the books I loved reading at an early age, and I wanted to try my hand at the kind of tale I had always loved when I was growing up. However, third and most importantly, the hero’s journey still works.

To understand why, let’s return to my first point: even Campbell did not invent the hero’s journey. He simply aggregated the patterns of stories already being told and identified certain universal themes within them that speak to us. He was not saying this is the right way to tell a story, he was saying these are elements that many successful stories have in common. Subverting tropes—a concept so regularly referenced that it has, in truly meta fashion, become a trope—is well and good, but there are some notions so universal to the human condition that they cannot help but resonate with people. Noble heroes have been failing to manipulative villains for several decades, or arguably centuries if one considers certain Shakespearean works, but noble heroes have been defeating manipulative villains for millennia. It is a concept at the core of the earliest campfire tales. That kind of history is powerful, and not taken lightly. I’d be bold enough to compare this to, say, a hypothetical new philosophical theory that challenged the works of Plato and Socrates. The new intellectual theory may indeed hold merit, since appealing to Plato’s and Socrates’ work on historical authority alone is unsound, but their philosophies have stood the test of time, have been challenged and tempered and molded by generations of intellectual discourse, while this hypothetical new theory would not have received the same degree of rigorous analysis and refinement yet.

Digressions aside, the hero’s journey works because many of us are the farmboy (or farmgirl). Our own lives are full of thresholds and transformations—adolescence, relationships, education, career, marriage, family, old age, and ultimately death. Our best hope is that we can do some good along the way, and the hero’s journey tells us that we can. The fact that the characters can face end-of-world conflicts and come out ahead is an indicator that we can overcome the trials in our own leaves. Yes, bad things happen to good people, but the hero’s journey acknowledges this. Boromir fell to the ring’s power, Biggs Darklighter got blown up, Cedric Diggory was murdered by Lord Voldemort. We don’t need to embrace nihilism as a result. Grimdark can be truly cathartic, as it’s easier to accept our own real flaws after seeing supposedly infallible heroes make even worse mistakes. The argument could be (and probably has been) made that the hero’s journey gives us the easy message, the comfort food, by telling us that things will be all right in the end, whereas tales that subvert such messaging deliver a harder but more important truth, that the world is an unforgiving place and that we will fail sooner or later. I hold, however, that the opposite is true. The message that everyone is flawed is the easiest message to hear in the world, because it means we don’t have to change. The message that we must persevere and do the right thing in spite of our flaws, that we have to accept the call to be a better person tomorrow than we were today, even as everything around us spins into darkness, is the one that truly challenges us to transform. Knocking a hero off a pedestal is easy; becoming a hero is hard. If there’s a chance that we can make a difference by doing so, it’s a message well worth hearing, and that is why the hero’s journey still endures.

Giveaway Information!

Prize: An eBook or Paperback Copy of Warrior of Light!

Starts: August 25, 2022 at 12:00am EST

Ends: August 31, 2022 at 11:59pm EST

Direct link: http://www.rafflecopter.com/rafl/display/79e197ac48/

Leave a Reply