Welcome to the The Rarkyn’s Familar by Nikky Lee book tour, made possible by the wonderful people over at Escapist Book Tours! Below you can find information about the author, the book, and an essay by the author diving into humanity’s obsession with monsters. Be sure to check both out!

About the Author

Nikky Lee is an award-winning author who grew up as a barefoot 90s kid in Perth, Western Australia on Whadjuk Noongar Country. She now lives in Aotearoa New Zealand with a husband, a dog and a couch potato cat. In her free time she writes speculative fiction, often burning the candle at both ends to explore fantastic worlds, mine asteroids and meet wizards. She’s had over 25 stories published in magazines, anthologies and on radio.

She has been shortlisted six times in the Aurealis Awards (Australia’s premier awards for fantasy, sci-fi and horror) and has won Best Fantasy Novella and Best YA Short Story. In 2021, she received a Ditmar Award for Best New Talent. Her debut novel The Rarkyn’s Familiar was published in April 2022 by Parliament House Press.

Book Blurb

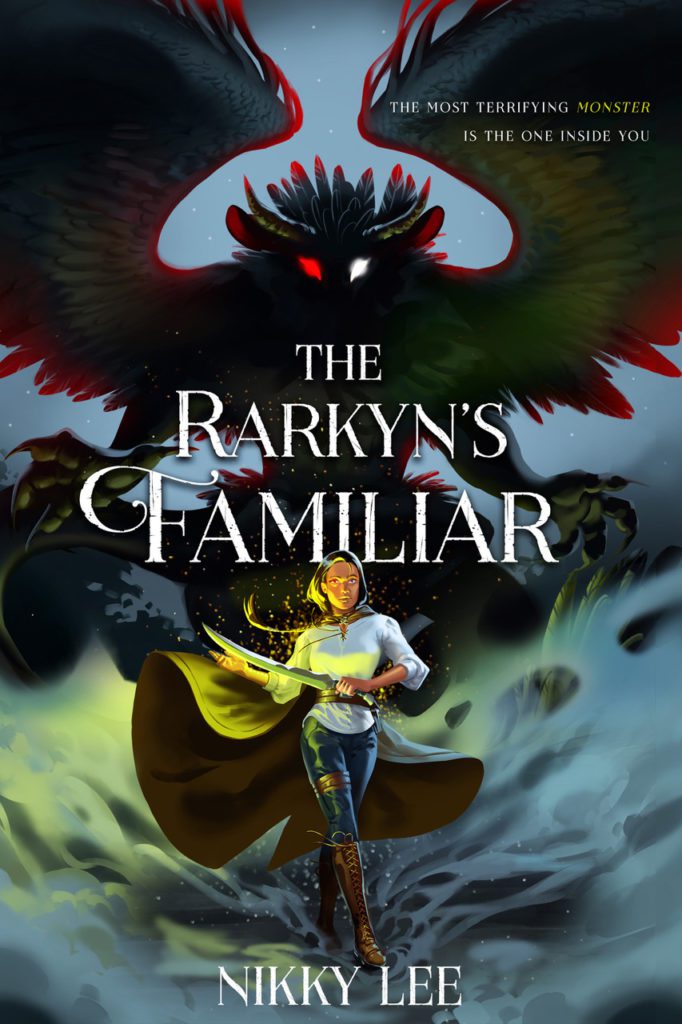

An orphan bent on revenge. A monster searching for freedom. A forbidden pact that binds their fates together.

Lyss has heard her father’s screams; smelled the iron-tang of his blood. She’s witnessed his execution.

And plotted her revenge.

Then a violent encounter traps Lyss in a blood-pact with a rarkyn from the otherworld and imbues her with the monster’s forbidden magic. A magic that will erode her sanity. To break the pact, she and the rarkyn must journey to the heart of the Empire. All that stands in their way are the mountains and the Empire’s soldiers—and each other.

But horrors await them on the road, horrors even rarkyns fear. The most terrifying monster isn’t the one Lyss travels with…

It’s the one that’s awoken inside her.

Book Information

Title: The Rarkyn’s Familiar by Nikky Lee

Series: The Rarkyn Trilogy

Genre: Epic Fantasy

Intended Age Group: 16+

Pages: 452

Published: April 19, 2022

Publisher: Parliament House Press

Content/Trigger Warnings:

Shown on page:

- Gratuitous violence

- Vomiting

- Gore

- Child/animal harm/attempted murder (non-human character, survives)

Alluded to:

- Vomiting

- Bullying

- Gratuitous violence

- Racism

- Sexual assault

- Gratuitous violence

- Suicide/self sacrifice)

Book Links:

Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/Rarkyns-Familiar-Rarkyn-Trilogy-Book-ebook/dp/B08L6YK3NP

Kobo: https://www.kobo.com/us/en/ebook/the-rarkyn-s-familiar

Barnes & Noble: https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/the-rarkyns-familiar-nikky-lee/1138770192

Angus & Robertson: https://www.angusrobertson.com.au/ebooks/the-rarkyns-familiar-nikky-lee/p/9781953539946

Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/54704737-the-rarkyn-s-familiar

And now for the author’s essay on Monsters!

The Monster as a Mirror

By Nikky Lee

It’s not every day I get to sit down and write a blog on the topic of monsters but here we are. As a writer of fantasy, often with dark and twisty themes, I’ve created, drawn on, adopted and reinvented my fair share of monsters, but it’s a rare thing for me to stop and think ‘why this endless fascination?’. What is it about monsters that draws me—and so many others—to them?

In ancient times, monsters were regarded as “divine displeasure”; creatures (which were often female) who went against nature and the gods. From the mother of monsters, Echinda, to the Gorgons, Sirens, Harpies, Chimera and Scyllaa and Charybdis who guarded the Strait of Messina, these creatures represented humanity’s fears and desires. The word monster itself, derived from the Latin monstrum, means ‘a sign or portent that disrupts the natural order’. In other words, from as far back as our earliest histories, ‘monster’ was synonymous with the Other—or rather, everything contrary to the dominant worldview of the time.

Quite a few years ago I studied the Anglo-Saxon epic Beowulf (‘studied’ applied somewhat loosely here, I was a terrible student). However, I do remember being struck by the character of Grendel. Terrorising the people of Heorot with murder and cannibalism, he is the first monster the hero Beowulf defeats. Described as a demon and a descendant of Cain; ‘a race of monsters exiled from mankind by God… From that family comes all evil beings’, Grendel is set up as a bitter outcast—a monster by heritage and birth. Through no fault of his own, Grendel was a monster before he began his killing spree, and I’ve always wondered how his story might have played out had he not been shunned to the outskirts of society and left to resent his lot. Of course, had that happened there’d be no story, let alone an epic oral tale, so monster he remains for the sake of story.

We see this interpretation of monster—the unnatural exile—played out in stories across the centuries, from Frankenstein and Dracula to Phantom of the Opera and even Murderbot. Interestingly, in more modern takes, the monster increasingly tends to include an element of choice. In the ancient world, monsters were monstrous by nature, even if they opposed the natural order. Today, monsters are not monsters because of what they are but who. They are monsters because they have chosen to flout the moral and ethical codes their society holds dear.

Which makes them all the more fascinating when we see them paired up next to a human character. For instance, in Guillermo del Toro’s Shape of Water, we see the Amphibian Man paired with Elisa, a mute woman who eventually becomes his lover. What’s curious about this monster-human pairing is how it reveals a sliding scale between human and monster—both in the monsters themselves (yes, plural) and within society. The Amphibian Man is the classic monster by nature—he has no choice in what he is; he was born an Amphibian Man. Elisa too is portrayed as monster-like; she is an unnatural exile and not by choice—her mutism sets her aside from the rest of her abled society. Both are portrayed sympathetically; beings who cannot change what they are for which the world punishes them.

Now here is where it gets really interesting.

In the world of Guillermo del Toro’s story, the love between the Amphibian Man and Elisa is seen as monstrous, at least to those in positions of power. However, to the viewer (and our two monsters) their love is innocent, portrayed as a beautiful, healing thing that helps Elisa find herself and a sense of belonging. When their safety is threatened by the powers that be, we’re left to ask: what is more monstrous, two exiles who have found solace in each other or the human antagonist who tortures, abuses and bullies others to realise his ambitions? What’s more corrupt, love or a lust for power?

The monster-human pairing in my own The Rarkyn’s Familiar works in a similar way, minus the romance. But where Elisa was born into a classic sense of monsterhood, Lyss slips from human into monster as she finds herself bound with forbidden magic to an otherworldly creature, outlawed by society, and on the run from those in power. When I wrote this story, I knew I wanted Lyss to start from a place of ignorance and have her worldview shift as she’s forced to walk a mile (and many, many more) in a monster’s shoes. As those miles pass, she finds common ground with her monster companion—with a few stumbles along the way—and discovers they are not so very different. The more she learns to accept the monstrous side of herself and her companion, the more their unlikely friendship grows.

As for her monster partner, Skaar the rarkyn (an avian-human hybrid), I created him as a monster out of water, if you will, much like Guillermo del Toro’s Amphibian Man. Separated from his home and community, Skaar is fighting for his right to survive. While he’s been labelled a monster by the society he finds himself in, the monsters he was taught to fear most as a kit were humans. This was what fuelled the start of the story: two races who each believe the other is the monster. (You can read more about it and the inspiration behind the rarkyn on my blog).

Perhaps what I love most about the human-monster pairing in stories such as mine, The Shape of Water, and so many others, is its ability to reflect truths our characters (and by extension ourselves and our society) don’t want or may not be ready to face. By the same score, the monster’s mirror isn’t always limited to the negative. In the right scenario, it can reveal some of humanity’s best traits in its ability to make us look beyond labels, embrace compassion, grow empathy and teach kindness. My favourite moments in many of these types of monster-companion stories are when a so-called monster finds their tribe; a person or people willing to accept them for who and what they are.

Traditionally, monsters represent the ugly, morally abhorrent aspects of the human condition. But perhaps because of our growing awareness of the damage our species does—pollution, climate change, mass extinction, poaching, slavery, murder, rape, war and so much more—a new monster has arisen. Often sympathetic, this monster reveals and reflects truths that help us grow. And when you meet this monster’s gaze, it deigns to ask, ‘who is the real monster here?’

Leave a Reply