Maps and Mapping in Fantasy by W.P. Wiles

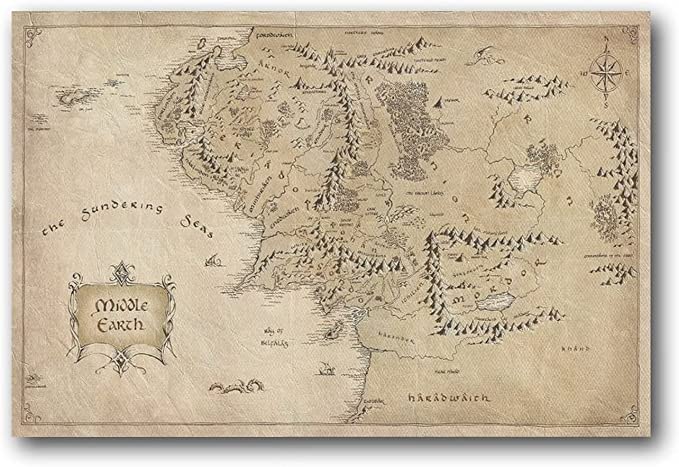

Like many others, I found my way into fantasy through maps. My mother read my sister and I The Hobbit, and I delighted in the map on the endpapers, drawn by Tolkien himself. It’s a rather curious map, as it happens, which doesn’t do a great deal of mapping. A great deal is happening at the edge of the page and beyond, and not much in the middle. But that’s the wonder of maps, their capacity to tantalise and withhold as much as they inform or explain.

Before long this interest graduated to the large fold-out maps at the back of my mother’s editions of The Lord of the Rings, but it feels unnecessary to go into too much detail about what those meant to me. As I say, many others have written about the powerful allure of fantasy maps in general, and Tolkien’s maps in particular. I could equally mention the maps in Le Guin’s Earthsea series, or the small yet lush full-colour maps found inside some Fighting Fantasy books, or the maps in Arthur Ransome’s Swallows & Amazons novels. It’s enough to say that in most instances, I reveled in those maps for a good while before I gave the text a go.

So it was with writing fantasy. As a child, when my ambitions to write mostly outweighed my patience for the work, I would spend hours making maps instead, creating the fantasy world where my epic would unfold, although I seldom committed much to paper of the epic itself. Instead my Parker Pen-stained fingers would be painstakingly adding scores of little lollipop trees to the boundless forests where no characters would ever tread.

There’s a thread of mapmaking in my literary novels – two of them have mapping efforts twined into their plots. And I always assumed that when I came to write a fantasy novel, of course it would have a map. What would be the point, otherwise?

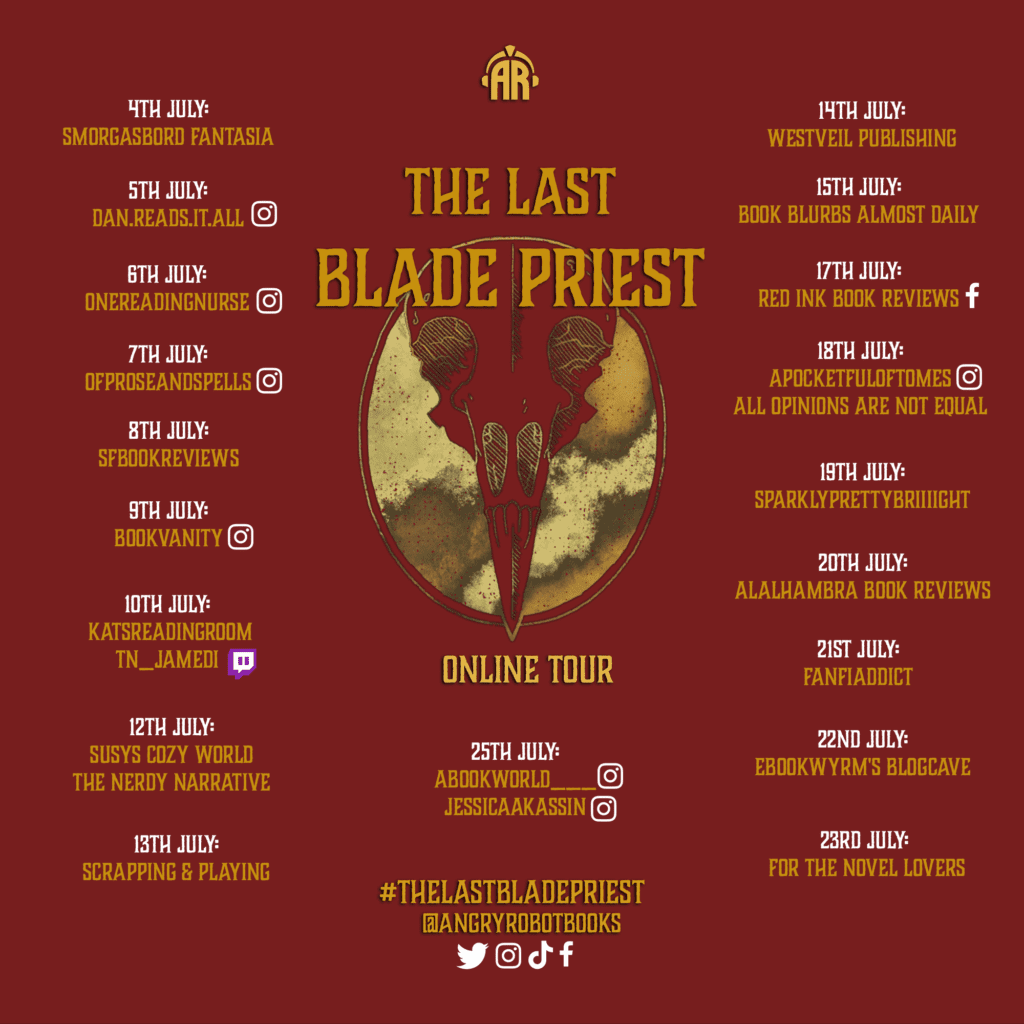

Well, here we are – or “You Are Here”, as it says on maps. My fantasy novel, The Last Blade Priest, is out this month, and … no map. We talked about it and decided against. I won’t deny that a map might have been useful. A lot of the book is about a journey into a strange land, and much of the story hinges on the location of a series of mountain passes. And there were maps, ones I had drawn myself to keep track of things, in pencil and on the computer (I recommend a program called Wonderdraft). But while my love of maps is as ardent as ever, I realised I had a few problems with them as well.

A fantasy map can be something of a spoiler. At the more generic end of the genre, you can glance at a map and guess the story begins in the highly detailed area centred on ’Umblefolk Farms, and will probably end up heading in the direction of the skull-shaped volcano in the Forbidden Wastes. Or, instead of giving the game away, that might in fact write a cheque too big for the story to cash. It would be quite a tease to show Darklord Peak on the endpaper and then have the characters go somewhere else entirely, and never mention it.

Or, in fact, you could have the story starting at the mysterious magical mountain in the forbidden desolation at the heart of the world, which is exactly where I start. But the people there know dangerously little of the world outside their fastness, and the people questing to reach them know little of what lies within. A map, a straightforward overview of the terrain between these very different world-views, might show too much; better, I thought, to experience the world on the ground, as the characters do. I felt that it was my job to provide the reader with a working mental map through words alone, filling it in as the characters discover it.

This sense of discovery felt quite important, because there is a map in the book, but we don’t see it. “At some time or another everybody, whether layman or specialist, needs a map,” writes Frank Debenham in the introduction to Map Making: Surveying for the Amateur (1936). (I did say I was into this sort of thing.) “Considering this universality of maps,” Debenham continues, “it is strange that the making of maps is still regarded as somewhat of a mystery …” And we’re off, into an arcane world of chain surveys and theodolite traverses. It’s a little like magic, or alchemy, wringing data gold from the base material of the planet’s surface.

It’s interesting to me that characters in fantasy novels often spend a lot of time journeying and crossing unfamiliar lands, and yet rarely do much to record their route. One might attribute that to the pre-modern setting of a lot of fantasy, before the age of discovery and the Enlightenment. But there were compulsive cartographers in the middle ages, too. And the maps in the books: who made them? To what end? In some cases – such as The Hobbit, where “Thror’s map” is an important document within the story, a delightful conceit – it is explained and incorporated; but often they just drop from an all-seeing non-diegetic Ordnance Survey in the sky.

So instead I wanted a story where the map is being made in real time, where the forces of reason are confronting the unknown territory of ancient magic, and naturally the weapon they bring is the surveyor’s tool set. Well, that’s not quite the only weapon they bring, but that’s another story.

Book Info:

Title: The Last Blade Priest by W.P. Wiles

Genre: Fantasy

Page Count: 400

Links:

Goodreads: The Last Blade Priest by W.P. Wiles

Amazon: The Last Blade Priest: Wiles, W P

Author Bio

W P Wiles was born in India in 1978. He is the author of three novels: the Betty Trask Award-winning Care of Wooden Floors (2012), The Way Inn (2014), and Plume (2019). When not writing novels, he writes about architecture, and he is a regular columnist for RIBA Journal. He lives in east London.

Author Socials:

Twitter: @WillWiles

Instagram: @wiles_books

Publisher Info:

Angry Robot Books

Twitter: @angryrobotbooks

Instagram: @angryrobotbooks

TikTok: @angryrobotbooks

Leave a Reply