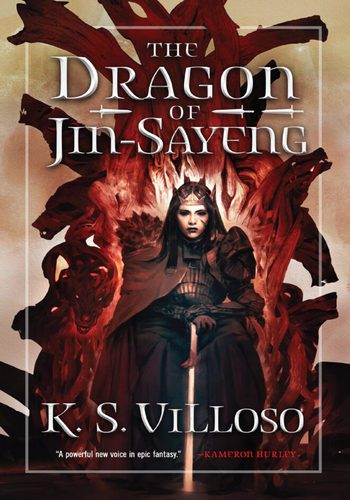

Rating: 10/10

Synopsis

Queen Talyien is finally home, but dangers she never imagined await her in the shadowed halls of her father’s castle.

War is on the horizon. Her son has been stolen from her, her warlords despise her, and across the sea, a cursed prince threatens her nation with invasion in order to win her hand.

Worse yet, her father’s ancient secrets are dangerous enough to bring Jin-Sayeng to ruin. Dark magic tears rifts in the sky, preparing to rain down madness, chaos, and the possibility of setting her nation aflame.

Bearing the brunt of the past and uncertain about her future, Talyien will need to decide between fleeing her shadows or embracing them before the whole world becomes an inferno.

Review

This review is mostly about The Dragon of Jin-Sayeng, with some general thoughts on the Bitch Queen trilogy as a whole. And while I’ve tried not to be too specific about anything, some of the things I discuss here may be potential spoilers for those who haven’t read it.

So.

With that in mind.

How to begin?

How do you write a book about individuals trapped within the strict confines of a system? How do you communicate the confines of such a system before the viewpoint character is even aware that they exist—before she grasps the utter, horrid totality of the world she’s mired in?

How do you write about the enormity of injustice inherent to absolute power if your only viewpoint character does not at first understand the greater context in her perpetuation of it?

How do you convey, in a first person point of view, that the most powerful people in this world radiate violence out from the fact of their existence? How do these people in the world cope with the fact that any one of them, for all that they are, for all that they can do, cannot hope to match the ruthless machinations of Empire?

Well.

It helps if you’re K.S. Villoso, the greatest character-writer alive today.

Like this book’s predecessors (and you should really read the other two books first), The Dragon of Jin-Sayeng builds a world enormous enough that every environment explored can serve as an externalization of its main character. Everything in this book is doing everything it can to demonstrate what Talyien is going through. Every instant conspires to let you in on her inner state.

It is this structure, the utter centrality of her lead character, that has allowed Villoso to spend her trilogy throwing obstacles at Talyien that embody both the blind spots in Talyien’s thinking, as well as the failures of imagination in the world around her. In this way, gulfs between characters become emotional, physical, and systemic all at once. The others around Talyien are inspiring stories and cautionary tales (and often both), and the legacy of those long left behind continue to haunt her.

It is difficult to summarize her emotional journey, in the best way. Like her physical one, it’s been all around the map. This has been a three-book buildup to perspective, the payoff to which trickles in slowly. A hint of awareness from Talyien, be it a comment, an excuse, a monologue—are perhaps the most rewarding part of the experience of this book (There is a monologue that comes in around the 2/3rd mark that I’d love nothing more than to commit to memory). It is an interrogation of the fantasy genre’s obsession with royalty, and the way the power dynamics inherent to such a setting are often sidelined without much question from the reader.

All this to say: we do not think about it because we do not want to. Just like Talyien.

This book marks the point where looking away becomes utterly impossible. It is the culmination of Talyien’s journey, which expertly implicates its readers.

The bulk of the book is focused on the way Talyien navigates her inextricable ties to the machinations of her Father, who still pulls the strings from beyond the veil of death. This man, this abuser, this externalization of the way she has been taught to hurt herself, becomes an apotheosis of a system he created to become a prison for his daughter. The inescapability of her own future, of her Father’s plans, drives much of the plot. It is primarily concerned with the navigation of Talyien’s feelings about the things that have been done to her. For her. In her name. It explores her feelings about life decisions made without her knowledge or consent. Decisions that remain tragically necessary, regardless of how she might feel about it.

And yet even so—even so! Necessary is not quite the right word for it. Talyien’s been doctored in to paper over the cracks made by the generations before her. What they are doing to her is only necessary because they made it so.

If this concept feels frustrating (in the best way) imagine that point being driven all the way out, and all the way down. From what the rulers of this land see as the lowest scribe, to what, in their judgment, is one of the most powerful people in their world.

He is a monster.

He is another monster.

And he wants nothing more than Talyien’s hand. Not her. But the power she possesses in her titles.

He wants nothing more than to cannibalize Talyien’s land, culture, and everything around her. And all the while he’s utterly indifferent. It is less about desires and more that this is all he knows how to do. He is how an empire shows its love.

He is a barely-held-together corpse that embodies every ideal Empires advocate, right down to the very fact that he is decomposing. He is falling apart at the seams. He is a shambling reminder that monstrosity is not an inherent state, but a product of creation. One that requires human life to sustain—innocent or otherwise, all lives are taken unjustly. Every scene involving him evokes discomfort. There were times I even had to put the book down and breathe deep.

The Dragon of Jin-Sayeng is a novel leery of the things we justify. It pulls no punches, it makes no excuses for an immoral action. It is a reminder that the act of feeling powerless is not the same as being powerless. It is about access to power and how people use it.

By the end of the book, everybody in this novel is made a monster, to some degree, and it is utterly, heartbreakingly human.

After all—we ourselves are made monsters in the same way. Whose hands built the device you read this on? How many injustices do we flinch from every day? How much power do we have that goes ignored?

We do not want to look at it. Just like Talyien.

This book expertly implicates its readers.

But. Perhaps the strongest element of this book is the way our heroes often react to its antagonist. The moments when his plans go sour. The instants of empathy he has no capability to anticipate or understand.

These are the things that make the struggle worth it. The brief glimpses of escape from everything. The moments in which Talyien is unburdened from expectation, from the crushing weight of a system all on her shoulders. A battle it is impossible to win.

This book is not afraid of murk, of darkness, but it is not quite grimdark. It does not delight in suffering. It is dark because the suffering is for something.

Talyien is the queen of a nation, and she fight so hard, sacrifices so much—all to have just one thing that’s worth losing.

And her journey is one of the best stories I’ve ever read.

Leave a Reply