Synopsis

Every great city has a soul. Some are ancient as myths, and others are as new and destructive as children. New York? She’s got six.

In Manhattan, a young grad student gets off the train and realizes he doesn’t remember who he is, where he’s from, or even his own name. But he can sense the beating heart of the city, see its history, and feel its power.

In the Bronx, a Lenape gallery director discovers strange graffiti scattered throughout the city, so beautiful and powerful it’s as if the paint is literally calling to her.

In Brooklyn, a politician and mother finds she can hear the songs of her city, pulsing to the beat of her Louboutin heels.

And they’re not the only ones.

Review

New York comes alive, each of its boroughs embodied in living person as a supernatural, otherworldly threat looms over the city.

Well, this review has been a long time coming. Very rarely do I find myself so conflicted by a book, but N. K. Jemisin’s latest, The City We Became, left my emotions mixed and two months later I finally feel I can deconstruct the reasons why. After finishing Jemisin’s The Broken Earth Trilogy a few years ago, I was stunned, enthralled, twisted. The Fifth Season and its sequels were so rich and complex, and—despite the tricky second-person narrative style—they gripped me enough to tear through all three books in a two-month period. So, with The City We Became, I had no idea what to expect, but I knew it wouldn’t be an easy read. Despite my suspicions being confirmed, I came out the other side both captivated and frustrated.

The City We Became is a book about New York, a city I adore, but N. K. Jemisin doesn’t pull any punches—this book is her New York City experience, from someone who has lived there. As a result, it’s very different from what I’ve experienced there during my multiple lengthy visits, though I appreciate this new vantage point greatly. It’s also different from the experiences of many New Yorkers or people who have passed through the city. But that is New York at its most essential: a melting pot of melting pots, where dozens of cultures and languages and experiences are smashed together—often to incredible results, and sometimes not so much. But there is immense depth to the city, physically and culturally, and it’s enriching to read it from a perspective, one so evocative and complex as Jemisin can deliver. Add in some truly crazy cosmic elements and this story starts to flip a familiar setting completely on its head.

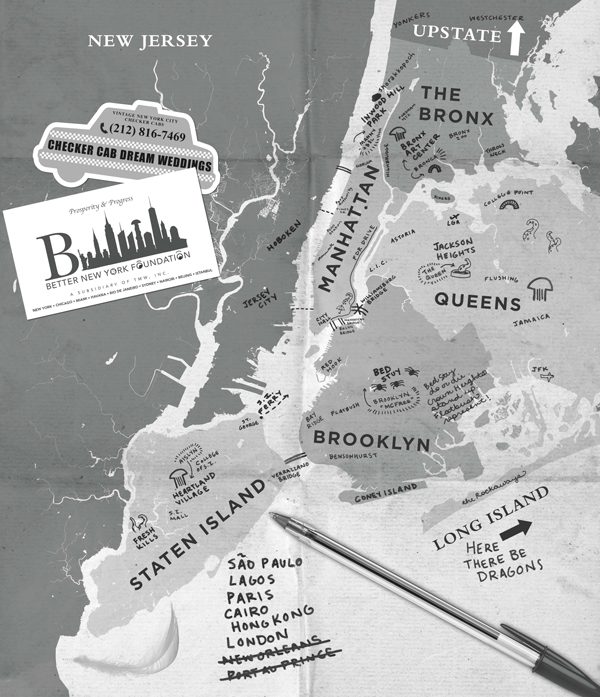

And that’s what this book is really about: subversion. Through a slow-burn narrative, New York comes to life as the living spirits of its five boroughs inhabit five denizens of the city; one person per borough, someone reflective of that borough’s essence, soul and personality. As a terrifying Lovecraftian threat starts to infect the city, each of the boroughs “wakes up” in a way that charmingly (and often hilariously) represents aspects of that borough. Bronx is brash, creative and full of sass; Manhattan is a natural leader, albeit flashy with a dark underbelly; Queens is humble, homey and multicultural; Brooklyn is lyrical and but overly proud; and Staten Island is the odd-one-out, a black sheep of the borough family (and also a source of criticism for me, but more on that later).

Overall, the way these “awakenings” unfold is great and well-described, especially the distinct conflict of logic and emotion and physicality. Each of them has to subvert their expectations of living a normal life ever again, while also combating the everyday horrors manifest in NYC and amplified by this new enemy. On top of that, being a human who had a life and memories but is suddenly overwhelmed with the immensity of becoming a borough is heavy shit, and most of the them go through rough transitions.

As these boroughs come alive and start to battle this infectious entity (appearing across the city as white, fungal tendrils and hive mind-like monstrous conglomerations), their duty as a collective city becomes clearer. Thing is, the infection is only visible to the boroughs themselves, but the essence of this intruder ripples across the city and its citizens. First, in the amazing opening chapter where the Williamsburg Bridge is toppled during a New York vs. Lovecraftian-whatever-the-fuck battle. Then later, as small inklings of this horrifying entity creep into each borough, infecting unsuspecting New Yorkers as it goes. The imagery of all of this was so vivid and it really sucked me into the atmosphere of a city under supernatural siege. As each borough witnesses these infections and fights them in various ways both physical, creative and intellectual, they finally come together to understand that New York as a whole is waking up, evolving into a Great City—and their job is to defend it throughout this transition.

Problem is, one borough doesn’t want any part of it: Staten Island says “Hell no” to the let’s-save-New-York-thing, cause New York doesn’t give a shit about Staten Island (and vice versa). This is one of my bigger issues with the book, but one I can’t criticize with absolute certainty. Staten Island is the only borough in New York I haven’t visited. But—and this is a big but—I felt that Jemisin was a bit harsh to present Staten Island in the way she did. (I don’t know the place intimately, so I’m speculating here.) But it’s hard for me to imagine that the essence of that place is one of racism or discrimination, at least to the point of self-isolation, or that they are just a bunch of stubborn white Republican-leaning immigrants (mostly from the UK). Sure, she generalizes all the boroughs, boiling them down into single human avatars, and this results in fairly broad portrayals of large areas. But Staten Island seems to get a pretty rough shake to come out as the only bad/villainous borough, although hey, I’m not a New Yorker, nor am I American. I could be totally wrong (you tell me).

Anyways, this leads me into Jemisin’s pretty overt political and personal beliefs, which come through the pages like a slap to the face at various points. White people are plainly the villains, lackeys of the villains or unsuspecting sheep in the supernaturally-infected herd. This is Jemisin’s experience, mind you, and she’s straightforward about that, so at least I can respect her honest perspective. I guess it’s difficult to write a story like this today without being somewhat political, and she clearly approached this project with an ideological framework in mind. The whole book is essentially a big “Fuck you” to Lovecraft and an attempt at reclaiming supernatural/cosmic horror for a new generation—and I applaud how well it challenges that history.

But, for me, a lot of the political elements came as a detriment to the story as a whole, and it often felt quite preachy. My main issue wasn’t necessarily from a content angle though, but more from a technical one. There was nothing subtle about Jemisin’s approach, and this resulted in some clumsy scenes, not-believable conversations and weird pacing.

Pacing is actually my biggest gripe with the book. I can look past how Jemisin wants to frame her New York experience, as I fully embrace other people’s experiences and want to know more about lives beyond my own. But coming from The Broken Earth Trilogy, which was masterful in its POV and timeline shifts, The City We Became feels clunky by comparison. Chapters often drag on for too long, such that the enticing cliffhanger from a previous chapter fades into a distant memory; many scenes that feel just right are dampened by others that overstay their welcome; and POV characters that I was aching to read more about as soon as possible are left hanging for a chapter or two more than I would have hoped. Overall, it gave me a slight feeling of fatigue in what was otherwise an incredibly cool narrative, with engaging concepts and characters.

Despite my conflicted feelings about the pacing and Jemisin’s heavy-handed political/cultural/social themes, The City We Became kept me invested from start to finish. Her prose is spectacular, and the way that she describes New York City is so detailed I felt like I was there, walking streets I’ve walked before. Her characters are also brimming with personality and history, such that they come alive on the page. And the tension of this strange otherworldly entity coming to Earth from another dimension to infect New York and subsume it—oh damn, it was so good! I want to know more about this invasive being: where it comes from and what its greater purpose is.

Honestly, N. K. Jemisin hooked me just enough with this one, and given her pedigree I’m on board for any sequels that she puts out. But I will approach them with the blinders off, knowing that I’ll probably be in for a hefty dose of political and social critique mixed with crazy supernatural tendril entities (the latter being what I want more of). Whatever the case, don’t go into this one expecting anything easy—you might hate it or love it, but hopefully this review can give you some idea of what’s in store. For now, I’m going to dig further into Jemisin’s back catalogue and see what treasures are waiting for me there.

Leave a Reply