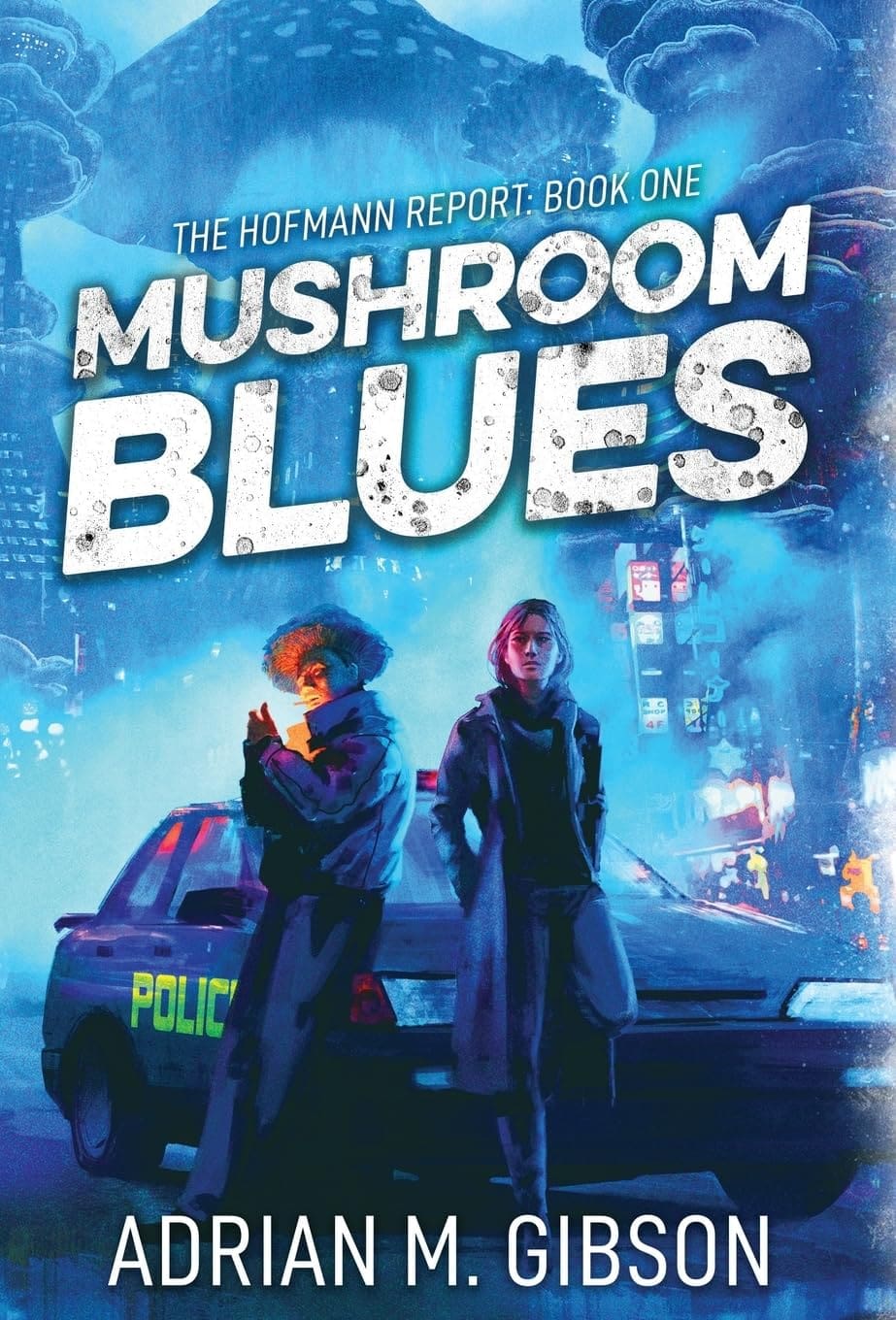

Quite a trip…

Synopsis

Two years after a devastating defeat in the decade-long Spore War, the island nation of Hōppon and its capital city of Neo Kinoko are occupied by invading Coprinian forces. Its fungal citizens are in dire straits, wracked by food shortages, poverty and an influx of war refugees. Even worse, the corrupt occupiers exploit their power, hounding the native population.

As a winter storm looms over the metropolis, NKPD homicide detective Henrietta Hofmann begrudgingly partners up with mushroom-headed patrol officer Koji Nameko to investigate the mysterious murders of fungal and half-breed children. Their investigation drags them deep into the seedy underbelly of a war-torn city, one brimming with colonizers, criminal gangs, racial division and moral decay.

In order to solve the case and unravel the truth, Hofmann must challenge her past and embrace fungal ways. What she and Nameko uncover in the midst of this frigid wasteland will chill them to the core, but will they make it through the storm alive?

Review

Wordbuilding in fantasy is hard. An author, at least one who wants to make the world feel lived in, feel real, must consider everything from the shoes people wear to the way the streets are lit. As a general rule, specificity is king: the more detailed you are (within reason, no-one wants to read pages on how traffic tickets are administered in your fantasy world, at least until you’ve won an award or two) the better.

How hard must it have been, then, for Gibson to write his debut fantasy noir, which takes place in a city full of “fungals” – literally a race of people with mushroom heads – a city which is mostly built from fungal growth? A book in which every single scene – from the spectacular (a giant mushroom which towers over the city) to the mundane – going to a restaurant, visiting a factory – must be carefully written to accommodate complex fungal biology and architecture, and where barely any commonplace object has escaped the fungal do-over? Frankly, as a writer myself, the brain hurts so much thinking about it that I think I sprained my neocortex. Whether it’s the body – the fungals have mushroom “caps” as heads and “gills” which emanate spores when they feel strong emotion, carefully replicating real fungal biology – to architecture – basic city materials are made from mycelium, furnishings are crafted in mould – by the end of this book you will be an expert in all things mycological.

Gibson is not the first to play around with mushrooms, or with bizarre biological worldbuilding (unsurprisingly, one of his strong influences is the striking visual bioscapes of Jeff VanderMeer) but for a debut to nail such a memorable cityscape is pretty remarkable. The closest parallel I can think of off the top my head is not a novel but a graphic novel series, Alan Moore’s Top Ten, which features a remarkably realised alternate Earth city built around the concept of every single person having super powers. Every page in Mushroom Blues is a lesson in worldbuilding.

But perhaps the most impressive thing about this novel is that its utterly unique, brain-bruisingly detailed worldbuilding is not itself the biggest achievement of this book. Gibson has crafted a tale of how fear of the other – of alienation from a race whose appearance instinctively repels – can be overcome through immersion and empathy, and as a study in this kind of character journey fiction it’s hard to beat.

The racist character in question is homicide detective Henrietta Hofmann, forced into exile from her hometown after traumatic events which we work out piecemeal throughout the book. She has made a new life in Neo Kinoko, the capital of the fungal nation of Hōppon. Neo Kinoko is a colonised city; the Coprinians (humans) have recently beaten the fungals in the Spore War and are now occupying their capital, which has barely started to recover from the devastation wrought on it in the war (on the excellent map Gibson includes in his gloriously well-packaged book, there’s a nuclear symbol occupying a large part of the north of the city which tells you all you need to know about how well the war ended for the fungals.)

Hofmann is not happy to be here, does not like the fungals, and does not like the fact that her new partner, Koji Nameko, is a fungal himself, but when fungal children start getting murdered and turning up in pieces, they must work together to find out what’s going on in this ruined city.

Hofmann’s journey, written in the first person in a brilliantly intense, emotion-filled voice, reminded me, interestingly, not of a book but of “awakening films” – films where the protagonist goes through a personal awakening. The obvious parallel is American History X – the white supremacist’s journey to realisation – or Training Day, where Ethan Hawke’s rookie cop slowly goes from naïve devotion to Denzel Washington’s detective to clear-eyed warrior, unwilling to stomach the corruption his mentor represents.

But Gibson has a new trick to this kind of awakening story that is pretty remarkable. He makes the reader, unwillingly yet inevitably, feel empathy with the racist, at least at first. As Hofmann begins her investigations, she wears a face mask and pops anti-fungal pills like candy, and it soon becomes obvious why. From fungal spores that emanate from the “gills” of the fungals to disturbing tunnels of mushrooms she must squeeze her way through, the entire city is one potential fungal infection. To those of us who once resided in mould-infested apartments (isn’t life in your twenties great), we have fairly traumatic memories of the darker side of fungi, and so despite recoiling at her racial slurs and xenophobia, we can’t help but to share her disgust every time a cloud of spores gets in her face – and then once we realise this we, like her, are forced to question our own prejudices.

Almost as forgiveness for recruiting us into his protagonist’s hatred, Gibson flips the switch as the book goes on: yes, the book gets darker and darker as Hofmann explores the seedy gang underbelly of the city and follows the trail of dead children, but as her attitudes begins to change – through immersion and empathy, the only two sure-fire ways to challenge culturally indoctrinated racism – so does the portrayal of the fungal city as seen through her eyes. Mushroom architecture and mould canvasses become beautiful, not foul; even the cuisine is suddenly renovated. The disturbing biology turns out to be the gateway to a metaphysical, spiritual, religious, astral – something weird at least – world of interconnectedness, glibly termed the “fungalnet” but more equivalent to quantum theory meshed with an acid trip in the desert (and yes, a character does do shrooms).

To read this book, then, is to go on a powerful journey with the protagonist and to have that journey replayed in your own senses through some of the most remarkable visual imagery I have found in a book; and it is a testament to how new worlds can shed light on old emotions. By the end, I almost felt cleansed, just like the protagonist, and for a debut to make the reader feel this way is applause-worthy.

With Mushroom Blues, Gibson has pulled off some of the best worldbuilding you’ll find in a debut to amaze, disturb and fascinate, yes, but also to bring you a tale that will tie itself round your emotions as invasively as the mycelium filaments that construct so many of his strange fungal environs. Come for the fungal growth, stay for the character growth: the only thing more impressive than Gibson’s colossal imagination is the size of his heart.

Leave a Reply