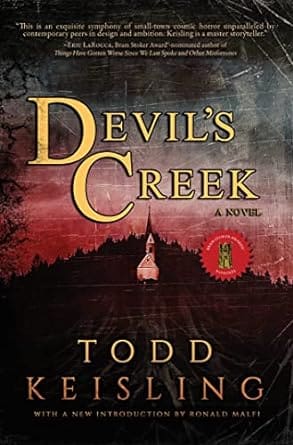

Synopsis:

About fifteen miles west of Stauford, Kentucky lies Devil’s Creek. According to local legend, there used to be a church out there, home to the Lord’s Church of Holy Voices—a death cult where Jacob Masters preached the gospel of a nameless god.

And like most legends, there’s truth buried among the roots and bones.

In 1983, the church burned to the ground following a mass suicide. Among the survivors were Jacob’s six children and their grandparents, who banded together to defy their former minister. Dubbed the “Stauford Six,” these children grew up amid scrutiny and ridicule, but their infamy has faded over the last thirty years.

Now their ordeal is all but forgotten, and Jacob Masters is nothing more than a scary story told around campfires.

For Jack Tremly, one of the Six, memories of that fateful night have fueled a successful art career—and a lifetime of nightmares. When his grandmother Imogene dies, Jack returns to Stauford to settle her estate. What he finds waiting for him are secrets Imogene kept in his youth, secrets about his father and the church. Secrets that can no longer stay buried.

The roots of Jacob’s buried god run deep, and within the heart of Devil’s Creek, something is beginning to stir…

Review:

“Give me some of that old time religion. It’s good enough for me.”

Oozing with both cosmic horror and small town disquietude, Keisling’s Magnum Opus “Devil’s Creek,” seamlessly blends the best bits of “The Children of Red Peak,” by DiLouie and “Little Heaven,” by Cutter. Within the confines of a quaint town in Kentucky, a malevolent force has taken root- it has slumbered, and festered, and is beginning to seep through “Stauford.” In “Devil’s Creek,” evil stirs once more. It’s insidious and horrific and sprawling and epic.

It’s 1983, and we find ourselves in the infamous “Devil’s Creek,” buried deep within the Daniel Boone National Forest. At the head of the Lord’s Church of Holy Voices, is Jacob Masters. Having fathered six children with some of his more “devoted,” followers, he plans to spill the blood of his “Lambs,” hoping to beckon forth a nameless God. This mass suicide is interrupted by the excommunicated grandparents, who rescue the children from Masters’ clutches- and wipe out the cult. The now traumatized survivors are forever immortalized as the haunted “Stauford Six.”

We then fast-forward three decades, and the somber news of Jack Tremly’s grandmother Imogene’s passing serves as a catalyst for his return to the small town of Stauford. He finds himself reunited with the remainder of the Stauford Six, their bond forged amongst tragedy and bloodshed, now tethering them together. However, with his return, an ominous specter also resurfaces, looming over the tranquil landscape, heralding the awakening of an insidious and all too familiar force. As the machinations of Jacob Masters set into motion once more, the stage is set for a cataclysmic confrontation. With fervent determination, Masters plans to reclaim his wayward flock, and sanctify the soil of Stauford with a baptism of blood and flame.

Whilst I could sit here and write pages upon pages on each of the Stauford Six, we both have things to do today I’m sure, so let’s focus on our protagonist. Jack’s art is inspired by the haunting dreams he is plagued by following his upbringing. Keisling uses him to comment on trauma- an integral part of horror- and how it can be faced as opposed to fled from. Unlike his half-siblings, Jack has turned his hurt into a successful career, enabling him to stay as far away from his childhood as possible. Of course, when he is forced to return, he’s rather reluctant, but when he and his family are threatened he follows in the footsteps of his grandmother.

Speaking of, Imogene, despite being largely absent aside from the excerpts from her journal between chapters, is a palpable presence throughout the narrative. Having once been a part of the cult herself, but now an indomitable spirit and fitting adversary to Jacob, she serves as a reminder that redemption is possible. On the other hand, Jacob is an embodiment of religious fanaticism run amok, and unlike Imogene, he will never cease to cast a long shadow over Stauford’s history.

After listening to a few interviews, I know that Kesiling has crafted a narrative that resonates on a deeply personal level. From the sunset town of Corbin, Kentucky, in which the Kentucky Race Riot 1919 took place, the novel also explores bigotry, indoctrination and manipulation. I recommend seeking out these interviews once you’ve finished the novel, it allows you to see Stauford in a new light.

A few reviews I’ve seen compare Devil’s Creek to Salem’s Lot by King, which I’m yet to read (I KNOW). In addition, I couldn’t help but be reminded of Herbert’s visceral prose when I encountered some of the gorier scenes. There is of course the aforementioned “The Children of Red Peak,” and “Little Heaven,” too in terms of plot. I’d also like to recognise however that “Devil’s Creek,” is wholly original and personal, and whilst I like to highlight similarities so that readers know what to expect, the parallels drawn here far from encompass this novel.

In conclusion, “Devil’s Creek,” with its richly drawn characters, thought-provoking commentary and atmospheric setting encapsulates the very essence of small town horror for me, and I can’t express how glad I am that Cemetery Dance rehomed it. I buddy-read this with the “Horror House,” book club, who were great company on this slightly fever-dreamish, but enthralling, horrifying, and ultimately moving narrative.

Leave a Reply