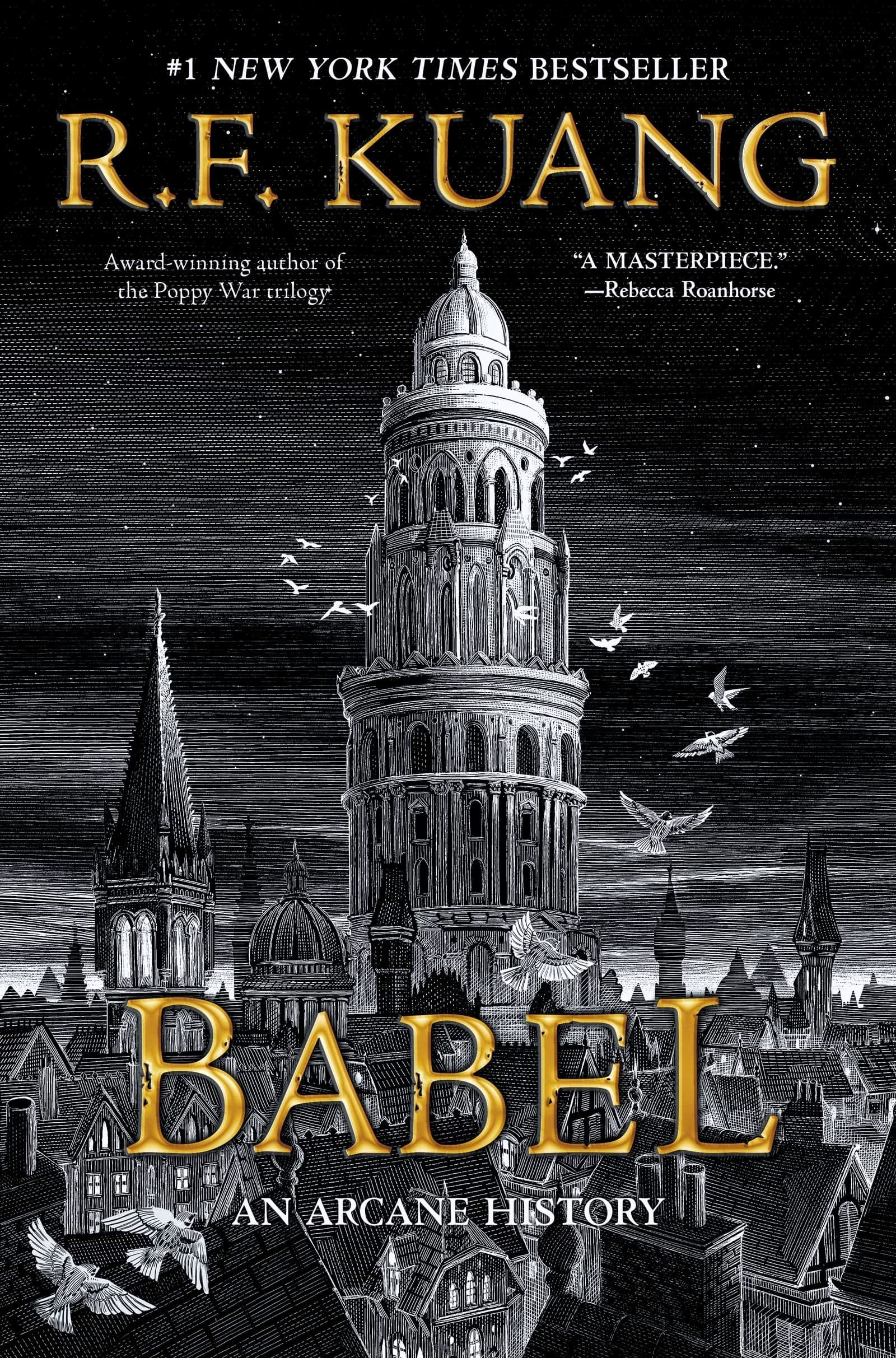

Synopsys

Traduttore, traditore: An act of translation is always an act of betrayal.

1828. Robin Swift, orphaned by cholera in Canton, is brought to London by the mysterious Professor Lovell. There, he trains for years in Latin, Ancient Greek, and Chinese, all in preparation for the day he’ll enroll in Oxford University’s prestigious Royal Institute of Translation—also known as Babel. The tower and its students are the world’s center for translation and, more importantly, magic. Silver-working—the art of manifesting the meaning lost in translation using enchanted silver bars—has made the British unparalleled in power, as the arcane craft serves the Empire’s quest for colonization.

For Robin, Oxford is a utopia dedicated to the pursuit of knowledge. But knowledge obeys power, and as a Chinese boy raised in Britain, Robin realizes serving Babel means betraying his motherland. As his studies progress, Robin finds himself caught between Babel and the shadowy Hermes Society, an organization dedicated to stopping imperial expansion. When Britain pursues an unjust war with China over silver and opium, Robin must decide…

Can powerful institutions be changed from within, or does revolution always require violence?

Quick Review

Babel is a brilliant historical fantasy novel, and a deeply uncomfortable read. R.F. Kuang writes it beautifully—whether she’s discussing lemon cakes or opium dens. I wholeheartedly recommend it, provided you are prepared to confront the topics of prejudice and revolution that are included within.

Full Review

I read Babel in two parts. Around the midway point I had to set the book down for a while, and only recently returned to read the second half. At the time I wasn’t particularly upset about that, because the first half of this book is slow, and after nearly three-hundred pages of Robin and his friends attending university, I was admittedly growing bored of the story.

However, the second half shifted entirely.

Let’s back up. Babel; Or the Necessity of Violence: An Arcane History of the Oxford Translators’ Revolution is a re-imagining of the 1930s and 1940s British Empire. Kuang doesn’t shake up historical fact too much, however she has created a brilliant magic system revolving around silver bars. When similar terms (but not quite identical ones) are inscribed on opposing sides, they act as Babel’s magic system.

Silverworking is a major part of this book. Kuang spends a lot of time explaining it and the words used on each bar. For example, when Wúxíng (a Chinese term referring to the imperceptibility of spirits and ghosts) and Invisible (unable to be seen; not visible to the naked eye) are etched into the silver—and the words spoken aloud—it can render the user invisible to others.

This gives the book’s magic a feeling of tangibility that I’m not sure I’ve seen before. Because each effect is rooted in some not-quite-perfect translation between languages, each “spell” has a sense of history and weight to it. It causes each silver bar to slow down the story as Kuang explains these details, but also enriches every silver bar from the mundane to the dramatic.

The story is told from Robin’s point of view. An orphan from China, is taken to England during the height of its power, after this silver revolution. He is made to study linguistics, and eventually finds himself at Babel, a translation and silverworking school within Oxford University. He develops close friendships with the others in his cohort, but throughout this he is never quite accepted the way he would hope. After all, he is a child of China in a country who—at this time—thinks the Chinese are less human: a resource to be used; a market for their opium. Robin is often told how lucky he is to be in England and to have risen above his birth.

This is the case for two others in his cohort as well, students originally from India and Haiti. Their languages are valuable to Babel, but their presence in England is merely tolerated.

This is the story of Babel. It is the tragedy of these students who desperately want to be accepted by their peers, but never will be. The act of translation—the magic system which is so ingrained into English society and has made them the most powerful empire in the world—is treated as an act of betrayal against the countries they come from. Robin and his friends struggle against this for a long time, until a sudden act of violence forces their hands. After this point, they decide that they must fight against the empire.

These events in the back half of the book, as I alluded to earlier, shift the tone dramatically. I had a difficult time putting Babel down at this point.

Although the first half was slow, I’m not sure that the second would have affected me as much without all of that set-up. Seeing Robin and his friends fight for equality and trying to prevent a war was genuinely moving—as was everything else around it. To elaborate on that would be to spoil major events of the book, however.

Babel is incredible. It is a story of efforts to change the system from within and actively fighting against it. The British Empire is not too different from the one in our history books, with an added magic system that adds to the story and streamlines the root problems and vulnerabilities of the empire. At the same time, Babel still takes the time to indulge in small moments: lemon cakes in the quad, studying in the library, or celebrating another year over drinks. It is equally unafraid to show things that are uncomfortable: opium dens, a dance where two girls are harassed, and a loss of self-identity.

I loved Babel, but I can understand why others may not share that opinion. In short, there were a few things about this book which I feel should be mentioned:

- The first half of the book is very slow-paced. I think it was the right choice, but that can be hard to understand while reading it.

- Babel is leaden with footnotes. Kuang uses them to describe different translations, notes about history, and so on. I enjoyed these, but I can understand why they may feel distracting at times.

- Silverworking is a major part of the book, and as a result Kuang spends a lot of time describing them & the translations. Again, I enjoyed this, but if you’re looking for something more action-packed I’m not sure it will resonate as well for you.

I will add that even I had some reservations about the story’s ending. I don’t think Kuang handled it poorly at all, but the final scenes were deeply uncomfortable. Perhaps that was the goal, however. No part of Babel is an easy read.

Leave a Reply