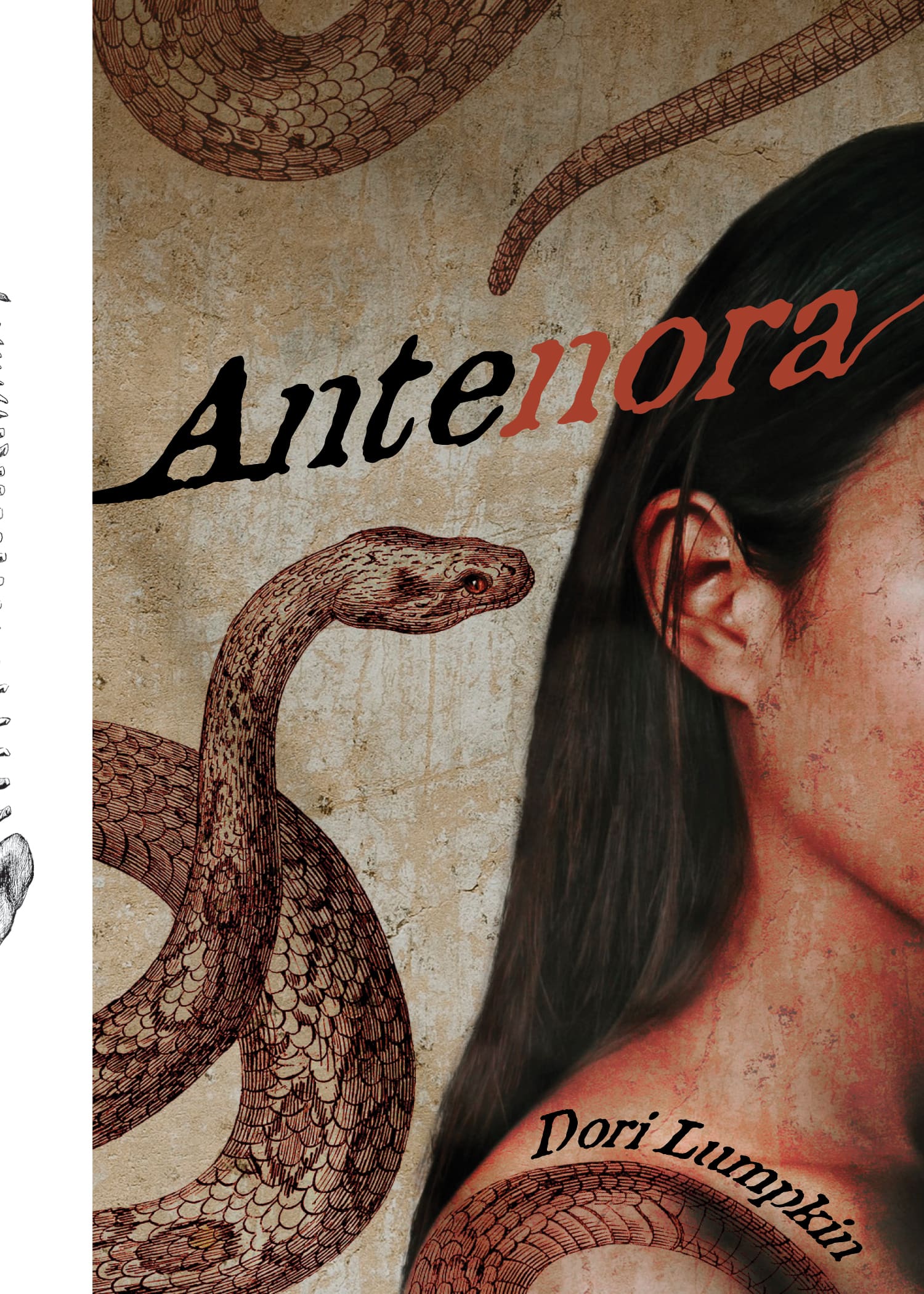

Synopsis:

Antenora: Dante’s ninth circle of hell reserved for traitors to their country.

What really happened to Nora Willet? The religious community of Bethel, Alabama can’t agree on the truth. They always said she was trouble. Later, they said she was possessed. Maybe she lost her mind, killing three people and injuring many others.

In a part confessional, part plea for Nora to come home, Nora’s childhood friend Abigail Barnes tells of another girl’s gruesome eighteenth birthday, of the time Nora may have fully revived a snake, of the intimacy of their private encounters at the lakeside, of Nora’s deliverance ceremony. Where, Abigail wonders, is Nora now?

In this tender and horrific debut, religious dogmatism sniffs out two girls whose innocent affections threaten an entire town and way of life, making one a traitor to a homeland in which only Abigail and Nora know the bittersweet truth. A homeland in which Nora can only say, “There’s a snake speaking to me, Abby-girl.”

Review:

I’ve read several excellent sapphic religious horror novels recently (The Woods All Black, When the Devil, Etc.) as well as some kick ass feminist religious horror (American Rapture) and all I can say is that I want all of it. Dori Lumpkin’s Antenora fits in neatly beside these other books, with its own almost medieval take, delivering an elegiac and brutal story about one girl’s absolute refusal to submit to her community’s demands.

In Antenora, very little of the horror stems from Nora’s supposed possession, or even from her violence, which flares up at unexpected moments and has real consequences. Instead, the horror is based on the place itself, on the rigid fundamentalism of the community’s faith, in the seemingly genuine belief in demons, devils, and spiritual possession.

These characters, from parents up to the trio of religious leaders, are painted as, well, devils, with Abby and Nora, our teenaged protagonists, as everyday kids just trying to make sense of the world. Well, and maybe resurrecting dead snakes?

Antenora is a book that raises more questions than it answers, and that’s a good thing. As readers, we’re submerged in the heady rush of teenage emotion, of young love, of adolescent questioning, and of memory. Pretending that any of these things can be objectively communicated would be silly, so instead we live within Abby’s consciousness.

The novel builds quickly toward its rather shocking conclusion, but the horror is ever-present, the dread dripping from the pages, but so is the longing, the the wish to speak for her lost friend.

In the end, despite (or because of) the horrific events happening outside of Abby’s control, there’s a ring of truth to Antenora. It also feels like a rallying cry to protect children from these regressive and damaging mindsets, a claim that the adults who stand by while children are hurt are the true traitors to any community, and deserve the greatest punishment.

Leave a Reply