Welcome to Dara!

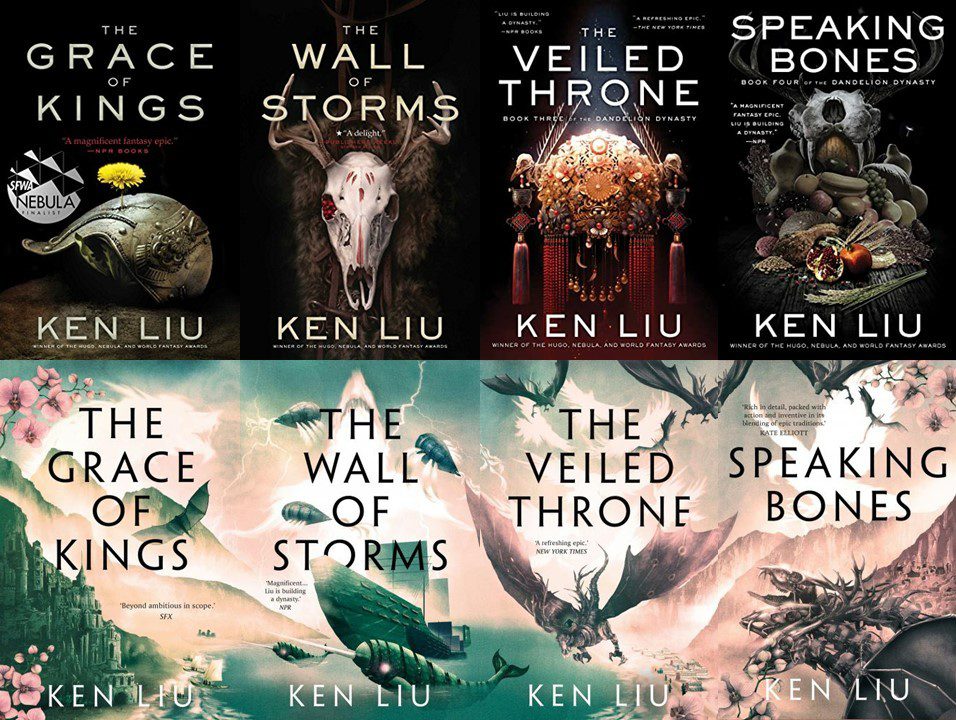

This series took up the bulk of my time and creative energy over a ten-year period. I learned a lot about myself as a writer, as a father, as a husband, as a grandchild, as a technologist, as a lawyer, and as a person. I can’t wait to take you and other readers from the opening lines of this book all the way to the final period after the last sentence in Speaking Bones.

A quick preliminary note: I invented the term ‘silkpunk’ specifically to describe the aesthetic in the Dandelion Dynasty series. (Other authors have used my term to describe their own books, and I won’t be talking about their uses. My only concern here is my definition, for my aesthetic.)

Silkpunk involves a technology vocabulary that uses bamboo, silk, paper, animal sinew, ceramics, feathers, materials of great historical importance to China and other East Asian cultures, as well as a technology grammar that emphasizes biomimicry, wind/water power, wooden architecture, balance with the local environment, an integrated view of the artificial and the natural – concepts central to East Asian traditions of engineering. It is, in the simplest terms, an alternative technology evolutionary tree based on East Asian historical antecedents and philosophies.

As a technologist, I had a lot of fun coming with up the silkpunk technology in these books: the submarines, airships, battle-kites, wax logograms, city-ships, electrostatic automata, etc. Most are based on historical antecedents, and I performed enough calculations and experiments to be comfortable that they should function, give or take an order of magnitude in the forces involved — close enough for fantasy engineering!

But silkpunk is not ‘Asian steampunk’. It is not ‘Asian fantasy’.

The ‘punk’ part is not a worn suffix devoid of content. To me, silkpunk is a new mythology of the experience of modernity because it is centered around a key punk project: re-purposing what was for what will be. These books are my rewriting of the narrative of modernity (and in the later books in particular, the modern American national narrative).

The Grace of Kings is the first step in this process of remythologizing modernity: a new understanding of the pre-modern order (the ‘what was’) The Wall of Storms and the later books tear that understanding down and rebuild it into something at once familiar and different: an alternative understanding of the meaning of the modern (the ‘what will be’).

But that begs a question: if The Wall of Storms, the second book, seems to be the start to the series proper (the construction of modernity), why did I write a whole book — TGOK — that only serves as a ‘prelude’?

Because a good house requires a good foundation. A driving impetus behind this series is my desire to challenge and interrogate the conventional narrative of modernity, which is often modeled on a particular telling of the story of my country, the US of A. The Story of America is most often told using allusions to ‘Western’ models (just think of how many aspects of American politics and national culture evoke images of America as a ‘New Rome’ and how easily we read Thucydides into every modern conflict involving America, with America starring as the ‘New Athens’). However, when you are constrained to one set of allusions, you’re limited in how you can push readers to see something new in a familiar tale or, even bolder, to change the narrative entirely.

Something radical had to be done. I decided to depart from the ‘New Rome’ or ‘New Athens’ model and instead evoke East Asian models in this fantasy epic recasting of the Story of America — and by extension, the narrative of modernity. Thus, I borrowed much of the plot of The Grace of Kings from the Chu-Han Contention, as interpreted by the historian Sima Qian, and built up a vocabulary of non-Western political allusions and precedents that could then be drawn on in the re-imagining of the epic of modernity.

This foundation is what allows the construction of an alternate vision of modernity, an imaginative edifice whose outlines would not come into focus until the later books, when the story moves away from reimagined history into pure invention. This is a vision of modernity no longer exclusively centered on what we think of as the ‘Western’ experience. Rather, it melds multiple traditions and myths important to me, from the Iliad to Beowulf, from Paradise Lost to wuxia, and transforms the Chu-Han Contention into the foundational political mythology of a brand-new, modern people.

The Wall of Storms is where all that effort begins to pay off. With most of the groundwork out of the way, I can get to the meat of this story about the creation of the constitution for a new people (a constitution, in my view, is not a document, but a set of stories that forms the core of a people’s self-perception, self-regard, and deepest values). The plot here no longer has a clear, specific historic analog. (Thus, identifying the people of Dara as ‘fantasy Chinese’ or the Lyucu as ‘fantasy Mongols’ or any people in these books as ‘fantasy [fill in the blank group]’ would be very much misguided.) Rather, the central concern of The Wall of Storms and its two sequels is a series of questions: How can a new nation built from a collection of diverse peoples compose a new constitution, agree on a new source of political legitimacy, rally around a new foundational mythology? How do we carry out a political experiment to build a more just society without creating more injustice? What weight should be given to the wisdom of tradition by revolutionaries? Is it a curse or a blessing that a new generation must contend with the weight of history they are born into and live with the decisions made by their forebears? Is a ‘perpetual revolution’ desirable or even possible…?

If those themes of the Dandelion Dynasty seem to draw on my experience as a lawyer, then the next set of themes are based on my life as a technologist. The Dandelion Dynasty is also a series about science and discovery. It’s epic fantasy with a heavy dose of scifi — I mean, Luan Zya literally proclaims, ‘the universe is knowable,’ a manifesto of the scientific view of the cosmos. I had some of my best writing moments in the discovery of the silkmotic force and the invention of the machines derived from its power. Many of the discoveries and inventions in this book are drawn from antecedents in China’s classical past; some are based on the work of ancient Greeks; some are modeled on the experiments of Ben Franklin; and still others are simply cut by me out of whole cloth. Being a technologist by trade, I love writing about discovery and innovation—and I’m pretty sure my readers enjoy reading about them too.

Before we go too far down these philosophical routes, however, I should note that it would be just as accurate to say that the Dandelion Dynasty is about young people flirting and partying and being silly and awesome garinafin-vs-airship set pieces and devious battle tactics — derived from history, to be sure, but also from the author’s experience in playing video games and watching football — and legalistic dirty tricks and deconstructionist mis-readings and fantastic engines constructed from silk and bamboo and giant capacitors humming with the power of lightning… I mean, sure, themes are important, but books always need fun.

I wrote the series because I had things I wanted to say and I wanted to have fun. Those are the only two good reasons to write a novel as far as I’m concerned.

—Ken Liu, 2022

The Grace of Kings, The Wall of Storms and The Veiled Throne are available now. Speaking Bones will be published in June 2022.

Readers can view Ken Liu’s commentary on The Grace of Kings and The Wall of Storms on Goodreads.

About the Author

Ken Liu (http://kenliu.name) is an American author of speculative fiction. He has won the Nebula, Hugo, and World Fantasy awards, as well as top genre honors in Japan, Spain, and France, among other countries.

Liu’s debut novel, The Grace of Kings, is the first volume in a silkpunk epic fantasy series, the Dandelion Dynasty, in which engineers play the role of wizards. His debut collection, The Paper Menagerie and Other Stories, has been published in more than a dozen languages. A second collection, The Hidden Girl and Other Stories, followed. He also wrote the Star Wars novel The Legends of Luke Skywalker.

He has been involved in multiple media adaptations of his work. A few recent projects include “The Hidden Girl,” under development by FilmNation Entertainment as a TV series; “The Message,” under development by 21 Laps and FilmNation Entertainment; “Good Hunting,” adapted as an episode in season one of Netflix’s breakout adult animated series Love, Death + Robots; and AMC’s Pantheon, with Craig Silverstein as executive producer, adapted from an interconnected series of short stories by Liu.

Prior to becoming a full-time writer, Liu worked as a software engineer, corporate lawyer, and litigation consultant. He frequently speaks at conferences and universities on a variety of topics, including futurism, cryptocurrency, history of technology, bookmaking, narrative futures, and the mathematics of origami.

Liu is also the translator for Liu Cixin’s The Three-Body Problem, Hao Jingfang’s “Folding Beijing” and Vagabonds, Chen Qiufan’s Waste Tide, as well as the editor of Invisible Planets and Broken Stars, anthologies of contemporary Chinese science fiction.

Liu lives with his family near Boston, Massachusetts.

![The Grace of Kings (The Dandelion Dynasty Book 1) by [Ken Liu]](https://fanfiaddict.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/51yQqCZqbaL.jpg)

Leave a Reply