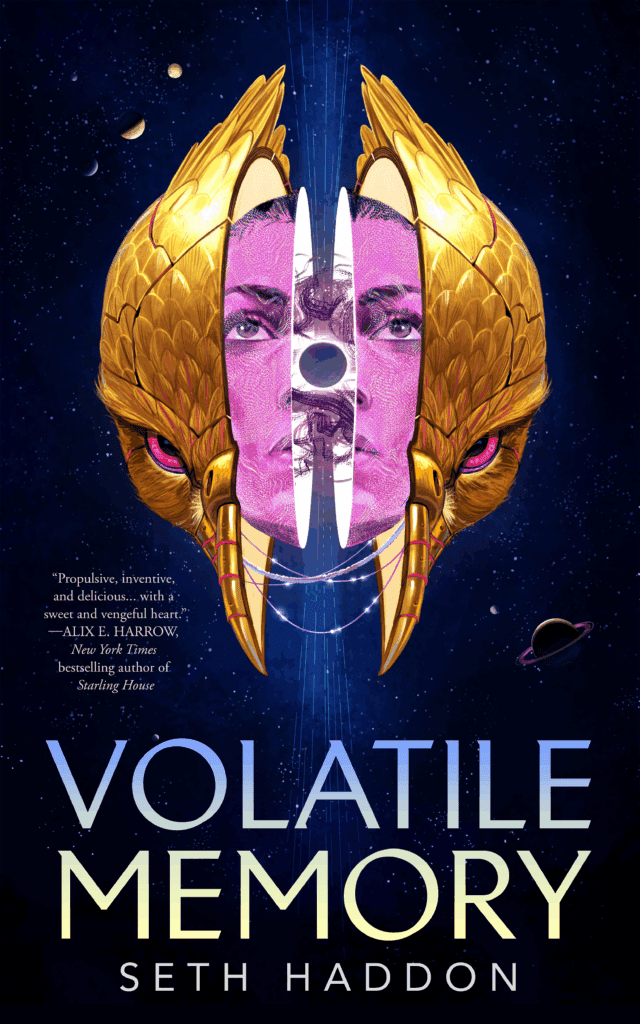

We all wear masks—some digital, some emotional, some made of military-grade tech, as in my novella Volatile Memory.

For as long as I can remember, I’ve been obsessed with masks—not because they conceal, but because they reveal. Across art, games, and fiction, I’ve found that masks don’t just protect identity, but reshape it. Often, the most profound moments come not when we put them on, but when we dare to take them off.

For my final high school art project, a decade ago now, I created a series of animal masks from resin, mosaic, and copper wire to accompany architectural oil paintings. The point was about the suppression of instinct—how civilization demands we neuter our animal selves. The masks, I argued, could liberate us. They would erase shame, loosen repression. At least, that’s how it felt to a closeted seventeen-year-old in Catholic school. I was certain that if I could wear another face, I could finally be myself.

I ended up experiencing that shift of personhood through a digital mask, of a kind. At eighteen, I played Dragon Age 2 for the first time. Ironically, the in-game character’s last name is Hawke. My Hawke was charming, self-assured—a contrast to how I felt. He had complicated family dynamics, a sharp wit, magnetic presence. I could romance a broody male elf with confidence. Hawke was persecuted for something innate—his magic—just as I struggled with parts of myself I hadn’t yet owned up to. I replayed the game for years, using Hawke as mirror, ritual, and rehearsal for the person I wanted to become. It was a small thing, but it helped me through a hard time.

Eventually, I came out and underwent the self-exploration most people do as teens in my early twenties and got a lot better (shame is an illness). But that’s beside the point. I’ve always been obsessed with masks. Now they’re showing up in my writing.

Game design was my initial calling. During that study, I began to understand that online avatars function like masks—crafted identities we wear to explore, conceal, or transform ourselves. In digital spaces, we try on new selves, test confidence, and explore hidden fears. As researcher Nick Yee (2004) notes, introverted players tend to create idealized avatars, while extroverts experiment with radically different identities. Baym (2010) suggests that digital spaces challenge the notion of fixed identity, echoing Goffman’s (1959) theory of the self as performance—one shaped by context and audience. Virtual worlds become emotional sandboxes, offering freedom through performance and distance from real-world constraints.

Digital avatars let people explore identities the offline world punishes. Many trans people use games to live out the gender they knew themselves to be before expressing it publicly. Gender in digital space becomes fluid—liberated from real-world constraint. The mask becomes a medium for self-recognition, not just self-concealment.

I think often about Mats Steen, a Norwegian man with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. He lived most of his life in a wheelchair, and his parents assumed he was isolated—until they discovered he had lived as Lord Ibelin Redmoore in World of Warcraft, forging deep friendships and heroic legacies. “In there, I feel normal,” he wrote. “My chains are broken.” His avatar wasn’t just escapism—it was expansion. His parents only realized after his death just how much of Mats lived through Ibelin. Sometimes our truest selves are found in fictional skins.

But this freedom is not without weight. Masks—digital or otherwise—don’t exist in a vacuum. They carry baggage. In online spaces, avatars are treated differently based on perceived gender, race, and appearance. A male player using a female voice modulator might face harassment, even with the same performance. Yee’s research shows perceived attractiveness influences confidence both online and offline. Our biases bleed into the virtual. Oppression isn’t erased, only refracted. The ability to express gender online can be liberating, but that liberation is filtered through systems that still privilege certain identities over others. Digital space expands possibility but doesn’t erase the politics of perception.

This dynamic—freedom through performance, but only within a biased frame—plays out across genre fiction, too. Zuko in Avatar: The Last Airbender adopts the Blue Spirit mask to act outside the rigid expectations of his family and nation. The mask—blue, like the Water Tribe, not Fire Nation red—symbolizes ideological shift. As the Blue Spirit, Zuko behaves in ways he never could as a Fire Nation prince: noble, kind, altruistic. The mask offers freedom through dissociation from his prior identity. But even here, freedom is temporary. The return to the unmasked self always comes with consequence.

The idea of masks as both liberation and burden continues in V for Vendetta. V wears a Guy Fawkes mask not to hide weakness, but to erase individuality. His anonymity is his strength. By erasing his individuality, he transcends the personal and becomes a collective avatar of resistance. The mask’s power lies in its anonymity—anyone can wear it, and therefore, everyone can become V.

But what happens when masks are mass-produced and intimately tied to a world’s economy?

Set in an ultra-capitalist future, Volatile Memory imagines a world where masks are ultra-common wearable technology. Characters don AI-infused animal masks that alter behavior, amplify instinct, and grant specialized abilities. Anonymity is a luxury no one can afford: Formal identity is reduced to genetic code in the Corporate Federation, so that all citizens are tracked via DNA. Facial recognition and the blurring of identity via masking is no longer possible, and so that power of liminal identity afforded by masks in other pop-culture scenarios vanishes in Volatile Memory’s world.

But, as inevitable as human nature, the donning of these masks results in a reshaped personhood. My protagonist, Wylla, wears RABBIT: a mask that enhances speed and hyperawareness, but also internalizes prey behavior. Caution becomes anxiety. Alertness becomes paranoia. And when she’s targeted by predators wearing OX and RATTLESNAKE, her instinct to flee isn’t just psychological—it’s encoded into the mask’s neural feedback.

Then Wylla discovers HAWK—an illegal, conscious mask. HAWK isn’t just software. She’s either a sentient AI or a fragmented human mind, uploaded and preserved. Through HAWK, Wylla doesn’t just gain access to new capabilities. Wylla shares her body with another person, and their identities co-evolve. Wylla starts uncertain, but as she’s treated like a threat because of her mask, she learns to perform—and eventually embody—that threat. Identity becomes a co-creation. A duet.

Wylla is trans, and her transness is a site of both vulnerability and resistance. In a world where legal identity is reduced to DNA, anything unquantifiable becomes suspect. Gender becomes state property. HAWK sees everything—memories, emotions, internalized transphobia—and cannot look away. Wylla can’t curate or explain herself. Each time she puts on HAWK, she risks being truly known. But she also becomes something more: not just a mask-wearer, but a person in symbiosis with another soul. In a world that reduces Wylla to data, and HAWK to commodity, they affirm each other’s full humanity.

Unlike every other mask in Corporate Federation, HAWK isn’t mass-produced. She isn’t anonymous like the Guy Fawkes mask. Her power doesn’t come from erasure—it comes from relationship. What does it mean to share a body with someone who sees you more clearly than you see yourself? What does it mean to love someone who can never have a body of their own?

These are the questions Volatile Memory tries to explore.

For now, I’ll leave you here: In both digital spaces and speculative worlds, masks offer protection, possibility, and transformation. They let us experiment with identity or access hidden behaviors. But real transformation—the kind that sticks—often happens only when we dare to take the mask off.

Sometimes the bravest thing we can do—online or anywhere—is to let ourselves be known.

This is How You Lose the Time War meets Ex Machina: Seth Haddon’s science fiction debut, Volatile Memory, is a sapphic sci-fi action adventure novella.

With nothing but a limping ship and an outdated mask to her name, Wylla needs a big pay day. When the alert goes out that a lucrative piece of tech lies hidden on a nearby planet, she calls on all the swiftness of her prey-animal instincts to beat other hunters to it.

What you found wasn’t your ticket out—it was my corpse wearing an AI mask. When you touched the mask, you heard my voice. A consciousness spinning through metal and circuits, a bodiless mind, spun to life in the HAWK’s temporary storage. I crystallized and realized: I was alive.

Masks aren’t supposed to retain memory, much less identity, but the woman inside the MARK I HAWK is real, and she sees Wylla in a way no one ever has. Sees her, and doesn’t find her wanting or unwhole.

Armed with military-grade tech and a lifetime of staying one step ahead of the hunters, Wylla and HAWK set off to get answers from the man who discarded HAWK once before: her ex-husband.

A Most Anticipated Book of 2025: GoodReads | BookRiot | Words & Brush Strokes | SheReads | BookTrib | We Are Bookish

“Propulsive, inventive, and delicious, Volatile Memory is a cyberpunk romance with a sweet and vengeful heart.”—Alix E. Harrow, New York Times bestselling author of Starling House

“Murderbot meets Firefly in a Thelma & Louise–style, high-tech, thrill-a-minute hunt for freedom, justice, and revenge.“—Library Journal

“Haddon combines sapphic romance, fast-paced mystery, and fascinating worldbuilding in his thrilling first sci-fi novel… Packed with combat, intrigue, and budding love, this is an exciting new direction.”—Publishers Weekly

“In Volatile Memory, Seth Haddon has given us something remarkable: a cyber-fabulous zoomorphic tale of breathtaking romance and adventure that is also a heartfelt—and sometimes heartbreaking—quest to trust, to love, and to seize one’s own authentic life.“—Ryka Aoki, author of Light From Uncommon Stars

“Compassionately written and juggling elements of intimacy and sweeping action, Volatile Memory is a surprisingly tender domestic tale dressed up as the best kind of pulp sci-fi…. It is a condemnation of the tyrannical past, a refutation to stasis. Joyfully, it picks apart the contradictions inherent to living, dying, and changing in a body, human or otherwise.”—Hiron Ennes, author of Leech

“A dark but tender story about love, vengeance, the masks we wear for ourselves and others, and the never-ending quest for a more perfect sense of self. It’s a beautifully intimate story set in the sprawl of space, especially recommended for fans of This is How You Lose the Time War.”—Yume Kitasei, author of The Deep Sky

“A sci-fi adventure wrapped in a future-tense queer love story, [Volatile Memory] follows the fate of tech hunter Wylla, whose latest acquisition is nothing but trouble. Good trouble, maybe. Haddon’s story blends high technology with compelling observations about personhood, identity, artificial intelligence, and the masks we wear. Especially the masks part.”—GoodReads

“A story of identity, physicality, action, and revenge: Volatile Memory is Seth Haddon’s first science fiction novel, and I hope it won’t be his last.”—Locus

“Puts an interesting spin on the question of what it really means to inhabit a body, and many readers will enjoy Sable’s righteous female rage.”—Booklist

“It can be difficult to find new science fiction that imagines unique and fascinating technology with real human stakes—Volatile Memory wins that prize. Add in a beautiful transhuman love story and a seething revenge plot, and you’ve got a sharp, tight narrative that had me dying to know what’s next.”—Bethany Jacobs, author of These Burning Stars

“Volatile Memory is a thrilling sci-fi revenge story filled with complex questions surrounding identity, gender, capitalism, and queerness. I loved how Haddon captured the haunting, sapphic romance between two profoundly different women. This is perfect for fans of This is How You Lose the Time War and Arkady Martine.“—Meredith Mooring, author of Redsight

“Propulsive and remarkable—biotech exploration at its finest and most intimate, pressing the seams of form and self and life in a world of suffocating regulation, especially on its women. I was instantly sucked in by Wylla and this unlikely love, with all of its wounds and deliciously righteous rage. This is sapphic revenge with a sharp, raw heart.”—Wen-yi Lee, author of The Dark We Know

About the Author

Seth Haddon is the queer Australian writer of Volatile Memory, Reforged, Reborn, and Reclaimed. He is a video game designer and producer, has a degree in Ancient History, and previously worked with cats. Some of his adventures include exploring Pompeii with a famous archaeologist and being chased through a train station by a nun.

Leave a Reply