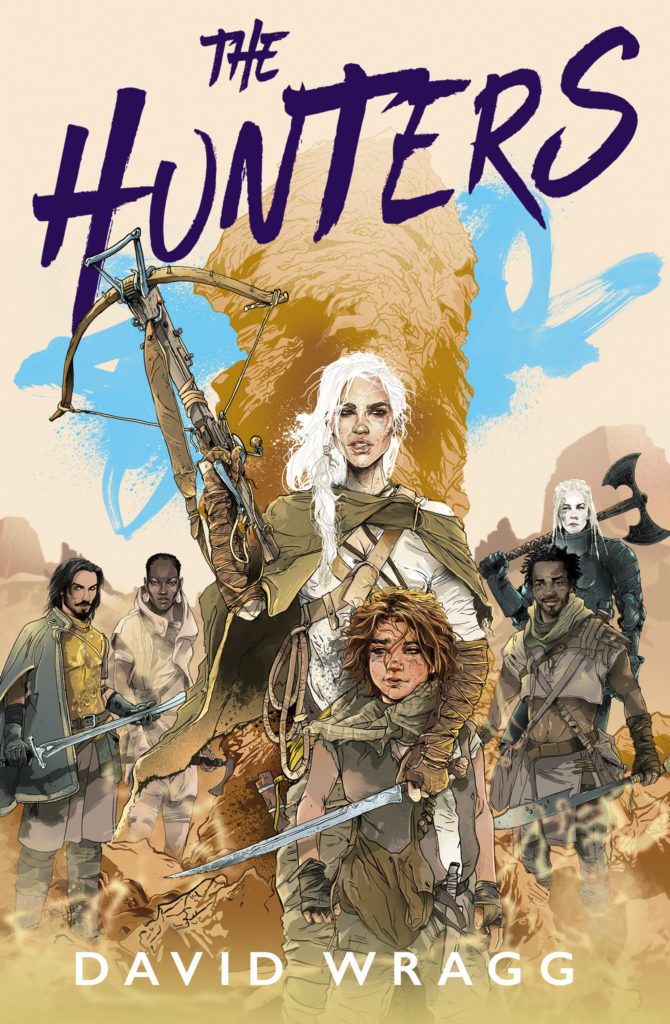

Thanks to HarperVoyager UK and Dave for allowing FFA the opportunity to share with y’all an excerpt from his upcoming fantasy novel, The Hunters (Tales of the Plains #1).

Hope you enjoy, and make sure to preorder a copy!

Cover Art by Gavin Reece

US Preorder

UK Preorder

Blurb

She’s on the run. They’re out to kill.

But what happens when you catch a hunter?

Ree is a woman with a violent past – a past she thought she’d left behind. After years of wandering, she and her niece Javani have finally built a small life for themselves at the edge of the known world.

But sometimes the past refuses to stay there, and Ree’s is about to catch up with her. This time, there will be blood.

For the land is in turmoil and professional killers have arrived in their town looking for an older woman and child, setting off a desperate chase through deserts, mountains, and mines. Ree will have to discover her former self if she is to keep them both alive.

From a master of modern fantasy comes a new thrilling trilogy, full of intrigue, bloodthirsty stakes – and a heroine who just won’t quit.

Author Info

David Wragg is the author of the Articles of Faith series and the Tales of the Plains trilogy. He lives in Hertfordshire, UK, with his family and an increasing number of animals.

Excerpt

THE HUNTERS – Chapter One

The woman who called herself Ree saw the feather of dust coming up the trail long before she heard the riders. The morning had been hard, as usual, and thankless, as usual, but her glow of small achievements was undimmed. She had greeted the dawn – the sun dances seemed harder each day, but she persevered – and done her rounds of the pens with Edigu, her foreman, checking and feeding the animals, before beginning the day’s tasks in earnest. The feed store was half done now, and by mid morning she’d dug out the last of the red earth where the stable would go. There was plenty of time left before winter, as the battering heat of the high sun gave joyless testament. Her pride at the construction milestone blunted some of her hissing frustration at the kid’s persistent dereliction. Once again, she’d drawn the morning’s water herself.

She was sipping tea on a battered stool in the shade of the half-stone, half-timber cabin at the stockade’s centre as the riders crested the last rise from the direction of the town, kicking plumes of dust into the streaky sky. Half a dozen riders, heavy-footed. She could guess who.

They loped straight through the open gateway of the stockade and reined in before the house. Six of them, all men, in their familiar long, split-tailed coats, bracers and greaves, their Guild-stamped breastplates grime-streaked, and dust masks pulled up almost to the broad brims of their helmets.

Ree leaned back against the timber wall and blew the steam from her tea as the lead rider edged his mount closer with a heavy nudge of his spurs. His little trophies rattled and jingled amongst his tack: ears, mostly, shrivelled and blackened, others impossible to identify but nonetheless tufted with hair. He tugged down his dust mask to reveal a square-jawed smirk.

‘Dawn’s fortune to you, Ree.’

‘And good morning to you, Kurush Mawn-Hunter. What brings you so far from the delights of the paradise terrace?’

‘Guildmaster Kurush, may it please you.’

‘My apologies, Acting Guildmaster.’

His smirk was undimmed, but a muscle in his cheek twitched. His eyes dropped to the mug in her hands. ‘You care to invite me in for tea?’

‘Sorry,’ she said with a small smile, its precise width calculated to hit the mark between deference and defiance. ‘This is the last of it.’

The smirk was indelible, as if carved into his blocky features. ‘Caravan’s due any time, maybe I can keep some back for you. You know I’m a man of influence. Just another reason to be nice to me.’

‘I wouldn’t want to put you to any trouble. Was there something urgent you needed to tell me? Six armoured riders at my threshold, must be important.’ Ree kept her eyes low. Where was the kid? Ridden off again? Her pony was missing from the corral. Was this about that?

Kurush sat back in his saddle and scratched at his helmet, revealing a line of trail dust across his brow and a pale stripe of thinning hairline. He caught her glance and pulled the helmet firmly back into place. ‘Word’s reached us at the Guildhouse that you’ve been . . . dealing . . . with the nomads.’

‘I’ve traded a few animals – they know their horses, as you’d expect. What of it?’

He leaned forward again, affecting concern. ‘Ree, my dear, those people are savages. They’re thieving murderers, and they’ll be coming back one day soon to slaughter you and steal all of this.

It’s just a matter of time. That old fella you’re keeping around, he’ll be the one to cut your throat in the night.’

‘Edigu isn’t Mawn, Kurush. The nomads aren’t Mawn. No matter how often you harvest them.’ She dropped her voice. ‘Gods know they’ve suffered most of all.’

He continued over her. ‘. . . Now, if you were to let the Guild staff your little farm properly, provide you with adequate security, we could see to it that you and that kid of yours were kept safe from any . . . untoward incidents.’

‘So that’s what this is about. Guild encroachment, again.’

Kurush put one hand on his dust-streaked breastplate, a picture of offence. ‘My motives are nothing more than a pure-hearted concern for your safety and that of your child.’

‘She’s not mine.’

‘Your relation aside, you should be taking care, yes? A lot of bandits in these hills, a lot of people who find robbing easier than working. Many of the other smallholders are happy to receive an enhanced level of protection, in exchange for—’

‘Kurush, do I need to fetch my writ of property? You know full well this land is titled to me, and the Guild has no claim on it.’

Kurush’s bonhomie fell away, and he fixed Ree with a steady glare. Behind him, the other riders shuffled and fidgeted, their horses swishing away predatory insects. ‘You’re still kinda new here, so maybe no one’s yet explained to you how things work. See, this ain’t the protectorate out here, this is the edge of the world. This is Guild territory. Now the governor down in Mahavrik, he and the Guild have an understanding. His outfit writes the titles and collects the taxes, but that’s as far as it goes. The Guild has what’s called a “free hand” in its matters domestic. And the, uh, protection of citizenry, that’s a matter domestic.’

‘Meaning what?’

‘Meaning you should think about things a little harder, Ree. You and I, we could help each other out. Not every man would look past that scar of yours, especially at your age, but . . .’ He tailed off, affecting a wistful gaze into the middle distance, but Ree could see the hard lines beneath his eyes, the checked anger at her resistance. She quelled the urge to snap, ‘And what age would that be?’, and kept her hand from reaching up to trace the line of the pale, jagged scar that ran from temple to cheek. She was past forty now. She supposed this kind of nonsense was inevitable.

‘Place like this, no one for miles around,’ Kurush lowed on, ‘no one in earshot. A band with ill intentions could do terrible things out here, and it might be months before anyone found the result. Only then would the Guild investigate, of course.’

He leaned forward in the saddle, fixing her with his mock concern once more. ‘It would be a real shame if my next ride out here was on the long-cold trail of your murderers, wouldn’t it, now?’

His coat hung open; one gauntleted hand gripped the hilt of the sabre slung from his belt. If he chose to ride me down, she thought, that would be it. No one would stop him – not his riders, not Edigu, not the kid . . .

From the corner of her eye she could see the fearsome crossbow leaning where she’d propped it against the water barrel beside her. Strung, loaded and cranked, she could snatch it up now, and give the Acting Guildmaster a first-hand taste of her enhanced level of protection.

. . . And not me.

Because, said a dark and cowardly voice at the back of her mind, you need this wretched man. You need his indulgence, and that of his blasted Guild. Glorious as it would be to punch a bolt through that little tin breastplate of his and out into the clear blue sky, his goons would hack you down and this place would be aflame by noon. You need him.

For yourself. For the kid.

Kurush leaned further forward in the saddle, yellowed leathers creaking. A bulbous fly had landed on the brim of his helmet, vile and iridescent in the sunlight. ‘So maybe,’ he drawled, ‘maybe, you want to think again about your level of protection?’

She let her gaze drop. ‘You’re right, of course. I must be prudent.’

He nodded slowly, his shoulders bobbing with the movement. A hint of the smirk had returned to the corners of his mouth, but she could feel the heat of his simmering anger at her impertinence. ‘Indeed you must, Mistress Ree. Indeed you must.’

The fly departed Kurush’s helmet and launched itself at his horse’s eye. The animal shied and he yanked the reins with a snarl. ‘Boys,’ he said, looking around at the restless riders, ‘we have here a reminder that mares can be troublesome and . . .’ he snapped the reins again as the horse tried to turn ‘. . . unpredictable.’ He cuffed the horse and it stilled. ‘They need a firm hand.’

Ree’s gaze flicked to the spur-rakes that marred the animal’s flank. She spoke before she could stop herself. ‘I find they merely respond to how they’re treated.’

She saw Kurush’s nostrils widen. He spat into the dirt and hauled his horse around. ‘We have other stops to make this morning, I’ll leave you to think on what we discussed.’ The smirk returned with a gleam of malice. ‘But you might not want to dally, Mistress Ree. Not with so many intriguing types asking after you and your child in these parts.’

‘What? What do you mean?’

‘First of the caravan’s outriders came in this morning, full of questions. Questions about a fine-looking, white-haired woman, and a child in her care. Can’t think who they meant. Maybe you’ll bring me a prompt answer yet, eh?’

They spurred their mounts back beneath the gateway, raising dust into the air, leaving Ree staring open-mouthed in the cabin’s shadow, unable even to call after them.

He couldn’t have—

That can’t mean—

Fuck.

She swallowed hard, balled her hands into fists to stop their trembling, and ran to fetch her sword. Moments later, she was mounted and riding hard for the gate, the sword at her hip and the crossbow on her back, and one thought alone in her mind.

Where are you, Javani?

*

Javani considered Behrooz a stupid man, which made him both great and terrible as a stooge. Such was his reputation, few would suspect him of the mental capacity to play the tiles well enough to gamble honestly, let alone under nefarious instruction. This was a man who had lost one foot to an avoidable mining collapse and an ear to a snakebite, and there were rumours that the snake had caught him sleeping naked and taken more than his ear. Javani disregarded the rumours; as long as he did as she’d told him, his body parts or lack thereof were no issue at all.

But now, suspended in the dark of the teahouse wind tower, perched on the little seat she and Moosh had carved, her legs braced, she was having second thoughts. She still had a perfect view of the game table, including the tile hands of most of the players, and although the rush of chilled air past her was distracting, it wasn’t altogether unpleasant, even if the wind’s moan in the tunnel stole away most of the conversations below. The morning outside was already bright and fearsome, and feeling her skin prickle in the tower’s cool gloom was as welcome as it was unfamiliar.

The problem was that Behrooz hadn’t looked up, even once. Not to check she was there. Not to ensure he didn’t play too early, or win a hand he shouldn’t. Not even just to stretch his ridiculous neck. Javani had the sinking feeling that he’d simply forgotten why he was there, why she had staked him, why she’d spent two hours the previous day drilling him in the plan. Why she’d pressed her aunt’s one true treasure into his grimy palm and made him swear not to lose it. He looked as though he was playing tiles, drinking and having fun. Either he had settled into the role like a master chancer, or her plan was buggered.

It had been such a good plan, too. The timing was perfect, catching the last of the overnight crowd once the triers and losers had been peeled off, when the hours spent in the cool of the teahouse and the musty spirits it served were beginning to blunt even the keenest sharp. There were always plenty of players overnight: off-duty miners, of course, some freemen, others bonded convicts, their crimes and sentences tattooed on their faces; Guild enforcers and resting caravan guards, awaiting the next departure; and the occasional itinerant professional gambler, chased out of every other venue on their inexorable path to near-exile. The tables were already piled with bundled scrip, some coin and even the odd miner’s treasure – a nugget of turquoise glinted in the lamplight on one, and another boasted a chunk of what one of the Guild heavies had loudly declared was ‘baby gold’. All Behrooz had to do was be Behrooz, right up until she gave the signal and he suddenly wasn’t. But for that to work, he had to see the signal.

A creaking and rattling above her announced another arrival, as did a shower of mudbrick dust. Moosh was coming down the little ladder. She hissed and waved at him to go back up, to get out before he made enough noise for everyone below to notice.

He either didn’t see or ignored her gestures, but fortunately the sounds of his arrival were covered by a commotion from the far side. One of the robed and bearded sect that plagued the main street had descended the teahouse steps and was attempting to drag out one of the players on another table. The wind and Moosh’s arrival blanketed most of their argument, but Javani gathered that the player was another member of the sect, and they were supposed to be heading out into the literal wilderness, not the moral variant. The younger man disagreed, but his fellow players were of the opinion that he had resigned forthwith and set about dividing his stake. Furious and ashamed, the zealots left.

‘Is he winning?’ Moosh whispered from beside her, his voice far too loud in her ear.

‘No,’ she growled back, more quietly.

‘So it’s working?’

‘I don’t know yet, dipstick.’

Moosh settled down on the perch beside her. His legs were shorter and he had to stretch to brace himself. ‘My dad was a sharp,’ he said, now matching her level. ‘Back in the city, before they made him give everything up. He made stacks of coin, but the big families didn’t like it and they made him promise to stop.’

‘Uh-huh.’ Javani kept her attention fixed below, her eyes on the ‘deserter’ tattoo on Behrooz’s cheek. He’d have to look up soon, if only to yawn. The smell of Confined Men was getting overpowering in the vent, and her eyes were starting to water.

‘In the end, he gave all the coin to the temple – he didn’t have to, but he didn’t want to make a fuss,’ Moosh went on. ‘And he promised not to gamble again, which was fine because he’d already won all the competitions, even the underground ones, so he didn’t need to do it any more. But that’s why he never came to the teahouse here.’

‘Uh-huh.’

‘But they still made him leave because he was really the lost son of the old Keeper, and the new Keeper was afraid he might try to take over, so that’s why we came north in secret.’

‘Moosh, your dad was a stonemason,’ Javani sighed. Moosh was an orphan, like her, although he’d at least had a chance to know one of his parents. His father had brought him north after his mother died of a fever in Moosh’s infancy, then he had perished a year before when a scaffolding collapsed at the Guildhouse. Moosh was now a ward of Terbish, the teahouse keeper; it was through Moosh’s unrelenting explorations that Javani had discovered the wind-catcher as the perfect venue for her scheme.

‘Exactly, that’s what he wanted everyone to think.’ Moosh paused, his babyish face scrunched in effort beneath his tangle of mudbrick-dusted hair, presumably thinking up his next tale. In the time Javani had known him, Moosh had claimed his father was a former commander of the Golden Lancers, a champion pit-fighter, and an assassin who had worked to topple the corrupt church of the Sink. He didn’t appear to see any contradictions. She didn’t begrudge him his invention; she’d been inclined to invent fantastical narratives for her own parents more times than she’d care to admit. All her aunt would tell her was that they’d been killed by Mawn, and in Javani’s weaker moments, the void of knowledge pained her.

‘What are you going to do if you win?’ Moosh asked, chewing at one finger. Javani suspected he still occasionally sucked his thumb. ‘It’s not like we can spend the scrip, we’re minors, not miners.’ He giggled.

‘Behrooz can spend it for us, and so can Ree.’ If it came to that, which she hoped it wouldn’t. ‘It’s not the taking part, Moosh, it’s the winning.’

‘It’s probably forged anyway, you know what these gamblers are like. My dad once said—’

‘Hush, this could be it.’

Behrooz yawned hugely, leaning back in his chair and issuing a silent howl. Javani tensed, ready to signal or wave, just to make contact, remind him that she was there. Her legs were beginning to tire and her backside was numb. He’d just lost another hand. His scrip was gone, the bleached and pitted blackwood of the table before him now vacant of stake. His fellow players were an odd-looking bunch, long-stayers, a couple wearing mail. They had fat bundles of scrip before them as well as loose coppers and a sliver of silver. She saw no Guild colours; Javani took them to be freelance muscle, probably waiting for the next caravan to pass before heading back south. One was due any day, this was the perfect time to pluck them. It was such a good plan.

And then, at last, the still-tilted Behrooz opened his gummy eyes and beheld Javani. She gesticulated wildly, mouthing furious curses, transmitting her orders with the ferocity of her expression. The light returned to his eyes as they widened.

‘Finally,’ she muttered. The wind had shifted beyond, and the moaning in the tower had mostly died.

Behrooz clomped back down on the forelegs of his chair, gave a theatrical swallow, and began patting his patchwork clothes. ‘Fellas,’ he said, ‘you just about cleaned me out. I’ve nothing left for food and board, won’t you show a little mercy on a luckless sort?’

Javani gave a narrow smile. That much was probably true.

‘Should have considered afore,’ one of the other players growled, one of the mail-clad. ‘Man shouldn’t risk what he can’t lose.’

‘You want any back,’ another snarled, ‘you play for it.’

‘But I’ve nothing left,’ Behrooz said, withdrawing his hand from his jerkin, ‘save this old stone my mama left me.’

The players leaned forward as the blue jewel clonked onto the table, and Javani leaned with them. She could feel their excitement.

‘Guess we could play a few more hands,’ the mail-wearer said. ‘If’n you cared to wager the stone.’

‘Now, boys, this here stone is worth more to me—’

‘We’ll stake you. Saba, deal ’em out.’

Javani checked her view of the players’ tiles as Behrooz glanced up in apparent consideration. She met his gaze with a smile of triumph.

‘Let’s spring this trap,’ she whispered.

Leave a Reply