Blurb

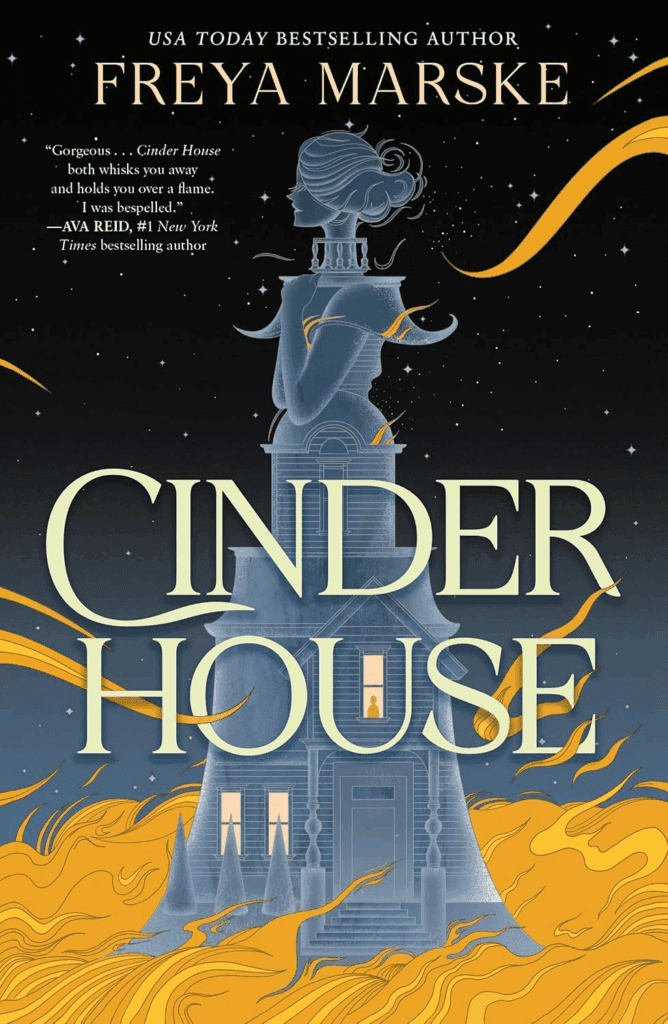

Sparks fly and lovers dance in this gorgeous, yearning Cinderella retelling from bestselling author Freya Marske―a queer Gothic romance perfect for fans of Naomi Novik and T. Kingfisher.

Ella is a haunting.

Murdered at sixteen, her ghost is furiously trapped in her father’s house, invisible to everyone except her stepmother and stepsisters.

Even when she discovers how to untether herself from her prison, there are limits. She cannot be seen or heard by the living people who surround her. Her family must never learn she is able to leave. And at the stroke of every midnight, she finds herself back on the staircase where she died.

Until she forges a wary friendship with a fairy charm-seller, and makes a bargain for three nights of almost-living freedom. Freedom that means she can finally be seen. Danced with. Touched.

You think you know Ella’s story: the ball, the magical shoes, the handsome prince.

You’re halfway right, and all-the-way wrong.

Rediscover a classic fairy tale in this debut novella from “the queen of romantic fantasy” (Polygon).

Excerpt

This newfound ability to leave was a secret that Ella would never, ever tell her family. It helped that they were used to not seeing her during the nighttime hours between dinner and midnight. Mostly they took themselves to bed, and Ella made sure the sheets were warmed and the water glasses full, so that she would not be needed before sunrise.

Her days became easier to bear because she knew the nights awaited. With the roof in her pocket she went walking, and was returned to the house at midnight.

Ella didn’t know why it was midnight, only that there was a palpable finality to that last strike of the clock, as constrict- ing and possessive and immutable as the physical boundaries of Ella’s haunting. The house might doze and allow Ella to roam, but it did not want her gone.

Knowing her time limit, Ella didn’t venture outside the city again. She wandered through parks deep in shadow and busy with the piercing sounds of night- birds, and discovered ponds symphonic with frogs. She returned to places she remembered, and sought out corners of the city she’d never been allowed to visit as a girl.

She stood on the bridges watching the purple mage-lights of the royal sorcerers hanging at the sterns of the official skiffs on the water, as their night patrol cleared the river of drowning-sprites and encouraged other watery fae to move along. Her father had once told her they were stringing up nets to catch mermaids. She still didn’t know if he had been mocking her or in earnest.

For the most part Ella was able to avoid having to touch or not-touch the living. No matter how dark the alleyway or unsavoury the neighbourhood, she was safe and unseen.

One bold night she followed some gilded carriages beneath the archway of a house so large it was almost a palace, and found herself at a masquerade in a private garden. Lanterns illuminated gowns sewn with seed-pearls and glass beads, and men whose coats sang with metallic braid, and mask after mask after mask: leather and brocade and silk, feathers and shells, monkeys and peacocks and sea-queens and cats and twisted, compelling imps.

It would have taken Ella’s breath if she had any.

Instead, after a few minutes of amazed staring, she found it too busy to stay. Too many people were walking unpleasantly through her, and an old fear of being lost and stifled in a crowd of impatient adults was dredged up from her childhood. Ella clutched the roof tile and fled back through the archway to a place where she could watch the arrivals descending from their carriages and lifting their masked faces, painted lips parting with anticipation, to the party.

She didn’t even consider entering the house itself. It wasn’t hers.

She’d tried that once: slipping through a wide-open door behind a man burdened with bags. But it had felt vastly im- polite, and the piece-of-house in her pocket went hot and strange before she’d had a chance to do more than glance cu- riously around the entrance hall. It seemed she was allowed to haunt her own house and also to exist in public spaces intended for all citizens, but not the spaces between other people’s walls.

An ideal place to linger was the night market. This was sprawled across the square before the old town hall, and its stalls opened at sunset. It was never too crowded for comfort, and on busy nights she would slip into a space between stalls and sit on the ground, and simply enjoy watching and listen- ing to people. If a good conversation walked by she could al- ways spring to her feet and shadow it.

“—even more expensive! But what choice do we have? That fool Mikeyla muttered about reporting the stallholder for smuggled goods, but I told her to keep her mouth shut if she wanted any spices in her food this winter.”

“It’s all about the Turnish Pass,” another woman said knowl- edgeably. “Some traders won’t risk it if they might get stuck in a skirmish. My Kurt’s brother in the army says they’re being squeezed up there on both sides. They’re expecting a bad late- winter freeze and it’s the only trade route that stands a chance of being kept clear before the thaw. If one side makes a grab to control the Pass . . .”

Ella dodged a group of young people walking inconsider- ately three abreast in order to keep up with the women. She was happy to learn about anything, but chatter like this made her world feel large again. Even if she would never see them herself, there were other cities than this, and trade routes which cut through moors and forests and snow-capped moun- tains, and people whose lives depended on the weather and the decisions of kings and the grit of armies.

“Oh, Leife,” said Kurt’s wife, as her friend slowed to a halt. “You promised me. No more pennies tossed away on this fan- ciful stuff.”

“Just a look,” said Leife.

The squat woman behind the stall tucked away a bundle of what looked like complicated mossy crochet. She flashed a wide, crooked smile of surprisingly sharp white teeth and surprisingly green eyes, both of which shone in the light from the huge twin candles that bracketed her stall. Ella thought again of mermaid nets.

“Fanciful they may be, but my humble wares will guaran- tee results,” said the stallholder. Her voice purred with a faint, unfamiliar accent. “What are you seeking, milady? Cantrip, charm, or potion?”

That caught Ella, who was on the verge of drifting off in search of other conversations. She stood at the opposite cor- ner of the table and peered over the wares as Leife hastily de- nied looking for anything in particular—well perhaps if she had anything for good fortune on a journey—yes, and how much was it, did she say? Ah, thank you kindly, but not today, they’re really just looking.

“Nobody wants to pay for good work these days,” the stallholder sighed as the two women took their leave. “And I suppose you’re just looking as well?”

Ella admired the gleam of river-polished rocks in a bag made of that same mossy crochet, and wished she could nudge the items on the messily arranged stall into a neater pattern. She drew back her hand before it passed through a spiky bundle of twigs and shells held together with silver thread and—was that hair?

“I said, are you just looking? Little ghost,” said the woman, “I asked you a question.”

Ella jerked her head up.

The woman’s gaze met Ella’s own with precision. Her eyes sat like green spiders in a cobweb of fine lines, sharp and curi- ous, and in the candlelight there was an eerie seeking quality to them which made the roof tile shiver in the same way that Ella’s wallpaper had shivered as the butterflies died.

“I,” said Ella. And was promptly silenced by the impor- tance of these, the first words since her death that might be heard by someone other than her family. Nothing profound came to mind. She resorted to: “How is it you can see me?”

The cobweb tightened with a smile.

“What’s your name, my dear? Your full name. You seem in need of someone to give it to.”

The muddle of possibility was still crowding Ella’s tongue. It was the only reason she didn’t blurt her name out eagerly in the sheer pleasure of being asked a friendly question with an easy answer.

But . . . those eyes were very seeking, and Ella had not lost all her instincts in death. In fact, she had acquired some. She looked again at the stall full of magic and let the wording of the question play through her mind.

“My name’s Ella, and that’s as much of it as I can afford to give away to a fairy, I think,” she said.

That got her a laugh, rich and hoarse. Ella didn’t look to see if anyone was glancing at this woman laughing to herself and talking to the air. She was afraid that if she turned away, the fairy and her stall would vanish in the instant before she turned back.

“Business is slow, you can’t blame me for trying.” The fairy’s hand lifted ruefully from a small blue-glazed pot, and Ella thought about the stories she’d read of sprites trapped in jugs and oil lamps. “We can stick to fair exchange. You can call me Quaint. How did you know?”

“You feel magical,” said Ella. On her guard now, she didn’t say she’d only met one sorcerer that she knew of, and Quaint’s magic felt different to Greta’s: more diffuse and more in- grained. “And it’s fairies rather than sorcerers who want your name to do things with.” She dared a smile, as Quaint looked more amused than annoyed. “I’ve read enough books to know that.”

“You’d be surprised how many people don’t learn the les- sons they should,” said Quaint. “And those who forget their lessons when they’re surprised. You certainly surprised me.” “Do you see others like me, around in the city?” Ella asked.

“Other ghosts?”

“You’re the first I’ve seen untethered in thirty years,” said Quaint. The sudden leap of eagerness in Ella was quenched before it had time to rise. It hadn’t been much, anyway. She was still too delighted at having anyone to talk to for an extra dollop of hope to make a difference at that moment.

“Could you—” No; that was too close to a request. “Do you know of any that haunt public buildings?”

“None as sociable as you, Miss Ella,” said Quaint. “You mustn’t have been dead long.”

“It’ll be four years, this spring.” Long belated, Ella remem- bered her manners. Even if you couldn’t trust a fairy, it was worth being polite to them. She spread her lavender skirts and dropped a curtsey. “A pleasure to meet you, Mistress Quaint. Even if you would like to trap me in a pot.”

“Ah, none of that, my dear.” Quaint grinned. “It was habit.

Fairy magic is mostly harmless to ghosts anyway.”

Mostly wasn’t the same as completely, Ella noted. But she still grinned back.

Leave a Reply