Good now! I am thrilled to present my stop for my good friend C.M. Caplan’s The Fall is All There Is tour with Escapist Book Company! Below you’ll find information about the book along with an essay about the nature of being a quadruplet from the author himself!

Book Information

The Fall Is All There Is by C.M. Caplan

Series: Four of Mercies #1

Genre: Science-Fantasy

Intended Age Group: Adult

Pages: 411

Published: November 1, 2022

Publisher: Razor Sharp Books (Self Published)

Content/ Trigger Warnings

Shown on Page (things clearly told to the reader):

- Profanity

- Violence

- Ableism

- Cursing

- Drug Use

- Age gap

- Self-harm

- Vomiting

- Infidelity

- Gore

- Minor kink/S&M

Alluded to (things only mentioned in passing or hinted at):

- Child abuse

- Child neglect

- Child harm

- Financial abuse

- Statutory rape

- Incest (to clarify: no actual incest, but there are recounts of tabloid rumors about it)

See Also

First Person Smartass • Sorry Princess I Only Date People Who Might Stab Me • But My Whole Body is a Weapon

Book Links

Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0BHDBD8M7

Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/62887419-the-fall-is-all-there-is

Book Blurb

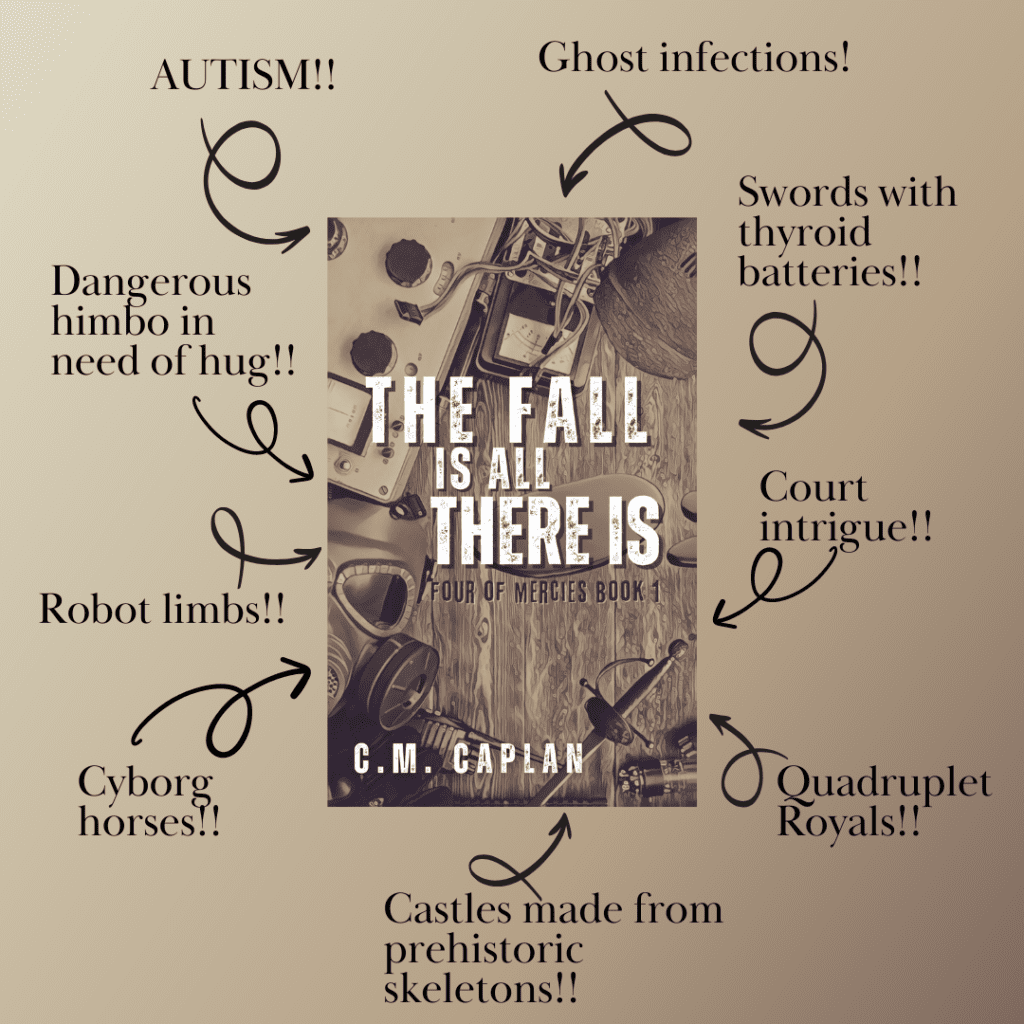

You never want to ruin a really good dramatic exit. When you flee home on a cyborg horse the exact second you turn eighteen, you don’t really expect to go back to the place you fled from, you know? But sometimes your old life hits you from behind.

Sometimes you spend years away from home, killing dangerous people who had the bad luck to get infected by a lungful of ghostfog, only to find out that your dad, the king, is dead, and now your siblings are ordering you back home for a high stakes family reunion.

But when you’ve got four heirs who are all the same age, the line of succession tends to get a wee bit murky. So in order to regain your independence, you’ve got to navigate a deadly web of intrigue, where every sibling wants your allegiance, and any decision might tear your country—and your family—apart.

Write What You Know – A Reflection on Being a Quadruplet

The first thing I ever learned was how to divide by four—and I don’t mean in a strictly material sense. One of the first pictures of me and my siblings growing up, after we all cleared of the health complications we developed due to being born three months early (and I finally figured out how to breathe and swallow my formula), is a picture of the four of us, all spread out in a row. I have a copy of it in my room with me as I write this. It’s one of my favorites—an illustration about how even your own birth can be about more than just you.

Some of my earliest memories involve negotiating the way the world received my identity as a quadruplet. I pin the blame mostly on the rest of the world. Because at no point did I ever feel like I had an identity outside of just myself. It was the rest of the world that had other ideas. From the moment I was born I had to convince the people around me that I was more than just one figure in a crowd of four—that I was not one quarter in a larger entity.

This, unsurprisingly, led to moments of acting out for attention, the way older siblings sometimes do when someone new enters the picture. Though in this case, in my mind, these were attempts to crowbar myself apart from the other three.

That said, I was never above using my status as a quadruplet for attention. It was always me who brought it up, much to the chagrin of the other three, if they were around. For a socially awkward, autistic child, a fact like that became like guardrails to keep a conversation lively—the easiest way to maintain that center of attention I was always vying for.

This resulted in a sort of feedback loop. I wanted an identity outside of just being one of four quadruplets—but the easiest way to receive attention was to bring up this fact to people who did not know.

Things only got more snarled as we got older. I was a late bloomer when it came to figuring out how to find my own friends, so I largely coasted around the same groups as my siblings, particularly my brother, in the hopes that I could find friends in the same places he could. But those friends were largely there for my brother. And my presence was, in hindsight, often rightly viewed with annoyance from him. After all, we were part of a larger entity, in other people’s minds. Anything I did was going to reflect on him, and vice versa. The more time I spent with him and his friend group, the harder it was for him to form his own identity. The world couldn’t let him, while I was around.

For a long time, this tension remained largely subconscious. I don’t even know if my siblings view any of this the same way I do to this day. I suspect it came to a head around high school, when a newly developed interest in fiction and writing snowballed into an identity I could define myself around that did not involve being a quadruplet.

I found myself not merely reading but dissecting works of fantasy and sci-fi. I consumed the stories that allowed me to escape my life and dove headfirst into the works of Robin Hobb, George R.R. Martin, Ellen Kushner, and Tolkien. I wanted to be like them. I wanted to write things. After a lifetime of attaching myself to my siblings, this was one of the first things I could call my own. And over time, these interests gradually congealed into a set of goals that led to me pursuing a degree in Creative Writing.

For the longest time, I avoided writing too much about siblings. I didn’t want to that part of me to make it to the page. I wanted this identity to be separate from the bind I’d found myself in as a child.

It was, of all things, a tweet, that really convinced me that it was time to dig into what the life of a quadruplet really felt like.

The tweet came from a twin. She was quote-tweeting someone else who said he felt weird encountering twins who were adults—as if that was an aberration. Something that’s not supposed to happen.

I don’t recall it word for word, but the sentiment to my memory illustrated a tangle I had never been aware that other people felt: “While I would never say I’m oppressed for being a twin the same way I am for being a woman, or queer, I think there is something to be said for the way having siblings of the same age is often treated by the world at large as if you’re bound spiritually, or have to share an identity. I never signed up for that.”

It got me thinking about the most famous twins or same-age siblings in fiction. None of them had their own identities either. They were downright goddamn interchangeable. To the point where often even their names were rhymes, or damn close to it! Identities began and ended at twin. And the few that did go deeper rarely strayed far from the concept that coming out of the same woman’s womb on the same day is somehow a deeper connection than any other kind you could ever have in this world.

So, I set out to write something with quadruplets. I’d just put out my debut, and it was time to shake things up.

I wanted people to realize that being a quadruplet or a twin or a triplet is basically just the same as any other kind of goddamn siblings. The only difference is the way the rest of the world treats you.

I’ve had an ongoing joke, while putting The Fall Is All There Is together: that I can’t wait for someone to read it and knock a star off because they “don’t understand why the four siblings had to be quadruplets” because it doesn’t exactly add very much to the book.

Which is the point.

They’re not spiritually bound. They have no more of a connection than anyone else would have to another sibling. Obviously, I had to throw in instances of the world treating them strangely. I was writing royals, so obviously I had to get a couple punches in on the nauseating trope that is the concept of “incestuous twins.” And other people occasionally treat the four of them like they’re inextricably linked. But for the large part the story revolved around its narrator, Petre Mercy, the youngest of the four by two minutes (an inversion of my own birth order, born first, two minutes before my brother, who came out fourth), trying to build his own life outside of both a court environment and a world that turns everything into a game of comparisons between himself and his siblings.

And you know what? It’s the best goddamn thing I’ve ever written. And I’ve never had more fun than I did writing this book. I’d let this side of my identity go unexplored for so long that it was like I was taking the release valve off a buildup of pressure, and it just took on a life of its own. All the things I never got to talk about much wormed their way in.

Write what you know, folks. Even when it scares you. Especially when it scares you. I never thought I could have so much fun incorporating quadruplets into a science-fantasy setting. But damn if this isn’t the coolest thing I’ve ever done.

And I am enjoying book two immensely. So, watch out for that.

About the Author

C.M. CAPLAN IS the author of The Fall is All There Is and The Sword in the Street. He’s a quadruplet (yes, really), and is disabled. He has a degree in creative writing and was the recipient of his university’s highest honor in the arts. His short fiction also won an Honorable Mention in the 2019 Writers of the Future Contest.

If you enjoy his novel, you can rate it on Goodreads or Amazon.

You can also subscribe to Caplan’s mailing list at cmcaplan.net to receive any free short stories, future updates, information, or sneak previews into future projects.

Twitter: https://twitter.com/thecmcaplan

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/thecmcaplan/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/thecmcaplanauthor

Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/21121094.C_M_Caplan

Giveaway

a Rafflecopter giveaway

Leave a Reply